When Michelle Cotton, artistic director of Kunsthalle Wien, invited art historian Margit Rosen to contribute to the exhibition catalogue of Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing, she asked her to focus on the 1960s. Rosen hesitated. Although she had spent many years researching the period, she knew it would be challenging to find pioneering female artists in the field.

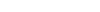

A quick search in her digital archive on “women in computing in the 1960s” confirmed the concern. The first images that appeared on her screen were a collection of women posing in computer advertisements. “What works for cars, apparently also works for computers,” she jokes during a keynote presentation at the symposium for Radical Software. Still, Rosen took on the challenge and uncovered the overlooked contributions of women in early computer art.

The show, on view at Kunsthalle Wien until May 25, features 50 female artists who experimented with the then-new machine through painting, sculpture, dance, installation, film, performance, poetry and numerous computer-generated drawings and texts spanning 30 years.

Cybernetic Serendipity: Creativity and the Computer

One of the most influential women in the field of computer art was the British curator Jasia Reichardt. In 1968, she organized the legendary exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA). It was the result of a three-year research project that began in 1965, after the German philosopher Max Bense suggested to her that she explore the role of computers in the arts.

“Her approach was both passionate and detached – a contradiction only at first glance," Margit Rosen explains in an email interview with The Overview. "She recognized the aesthetic and conceptual potential of the computer, but noted, with sober clarity, that its impact had so far been greater on the sciences than on the arts. More crucially, and in contrast to many curators and theorists of her time, she did not confine her attention to the device itself, the computer, but looked instead at the epistemological framework in which the technology was embedded: cybernetics."

Rosen, who works as the Head of Collections, Archives & Research at ZKM/Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, further adds that Cybernetic Serendipity was "not a celebration of the machine, but a layered exploration of key concepts such as communication, control and feedback. Many of the exhibited works had little to do with computer technology in the strict sense. It was precisely this conceptual broadening of scope that made Reichardt’s curatorial approach so distinctive.”

Curator Jasia Reichardt introduces the 'Cybernetic Serendipity' exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1968.

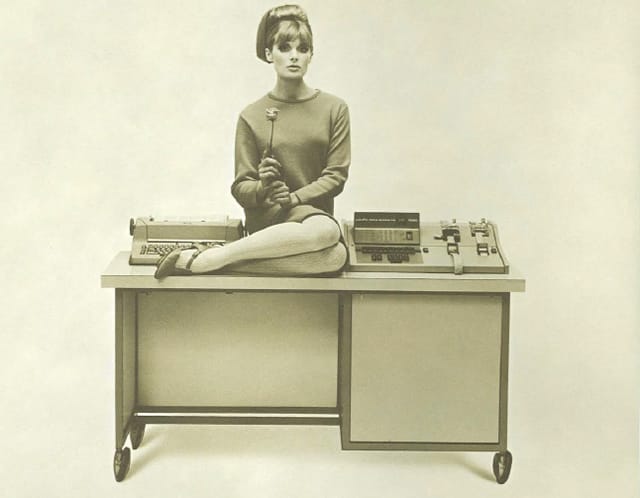

Random Dances by Jeanne Hays Beaman

The exhibition also featured 5 female artists, one of them was Jeanne Hays Beaman, a professor of dance who pioneered computer choreography at the University of Pittsburgh in 1964. Together with computer scientist Paul Le Vasseur, she created a basic dance-randomization program in the university’s proprietary code language.

They input 20 distinct time variations, 20 unique spatial directions, and 20 various movement types into the computer, which generated 70 dance sequences described in words, all within four minutes. The printed output gave dance directions such as: "Three medium beats, half turn clockwise, or arc backward".

As the catalogue of Cybernetic Serendipity reads: "For example, in the film Stationary dance the computer picked at random the place on the grid where each dancer starts. All successive space areas remained the same in this particular dance. Other possibilities are revealed by the titles to dances such as Cluster at the centre, Once off stay off, Circling counter-clockwise in which each new command moves the dancer around the stage grid, and Front and back, for which there are no lateral space commands.”

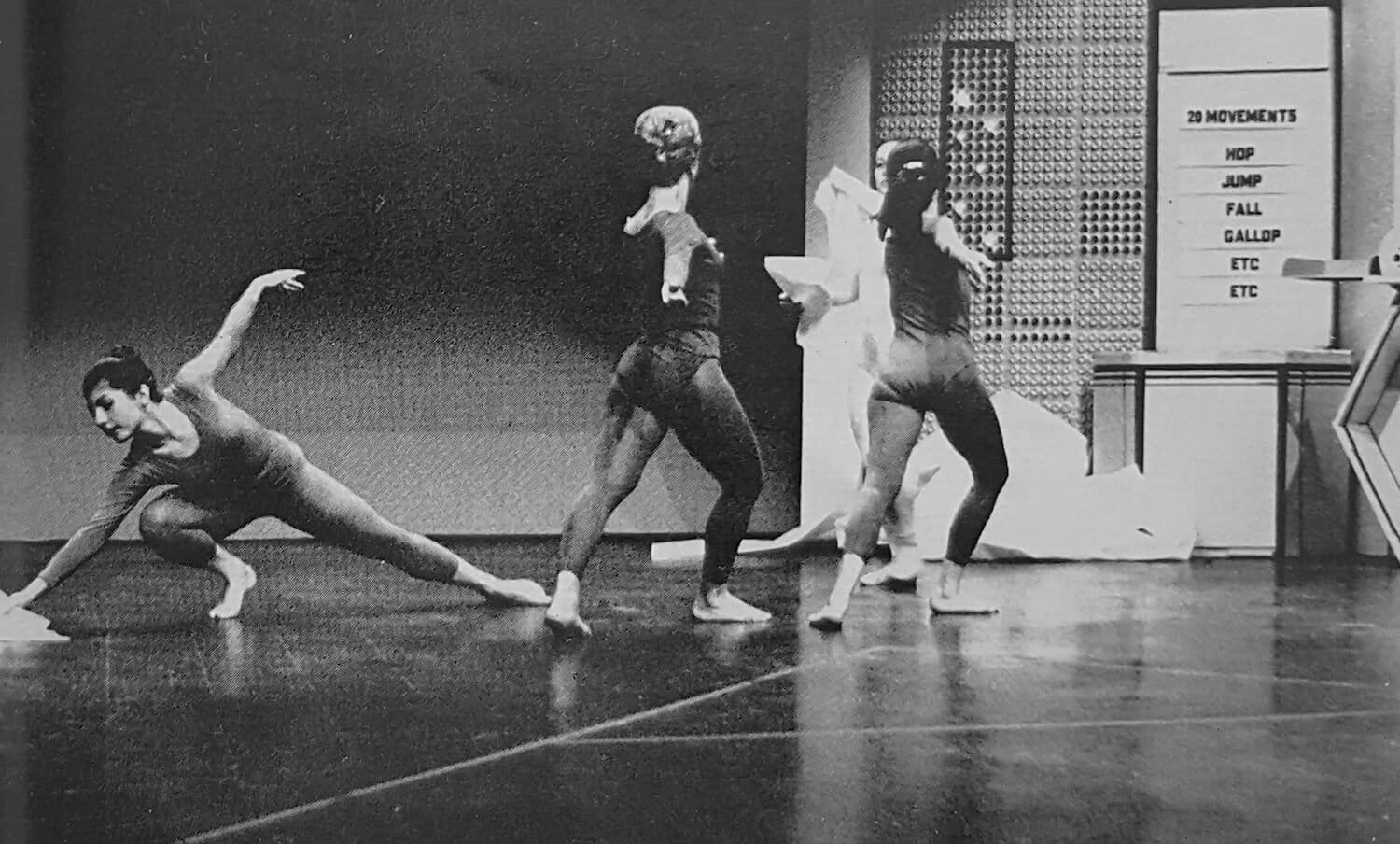

Alison Knowles: The House of Dust

Alison Knowles, another female artist in the field, and a founding member of the Fluxus movement, created computer-generated poems like The House of Dust in 1967, following a workshop led by composer James Tenney. For the piece, Knowles used four word lists, arranged algorithmically to define each “house” by material, location, light, and inhabitants.

Computer poetry itself dates back to the 1950s, and while it resembled earlier chance-based methods from Dadaism, what fascinated many poets was the idea that a machine—an “electronic brain”—might possess something akin to consciousness.

Margaret Masterman: A Japanese Haiku

Similarly blending computation and language, Margaret Masterman was a major figure in natural language processing long before ChatGPT. Unlike most linguists of her time, who focused on syntax, Masterman explored semantics and the ambiguity of language, challenges we still face today in AI. At the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition, she collaborated on a project that generated Japanese haiku using semantic combinatorics. She described it as a new 'folk art'—playful, accessible, and open to non-experts.

Scientific Art by Judith Prewitt

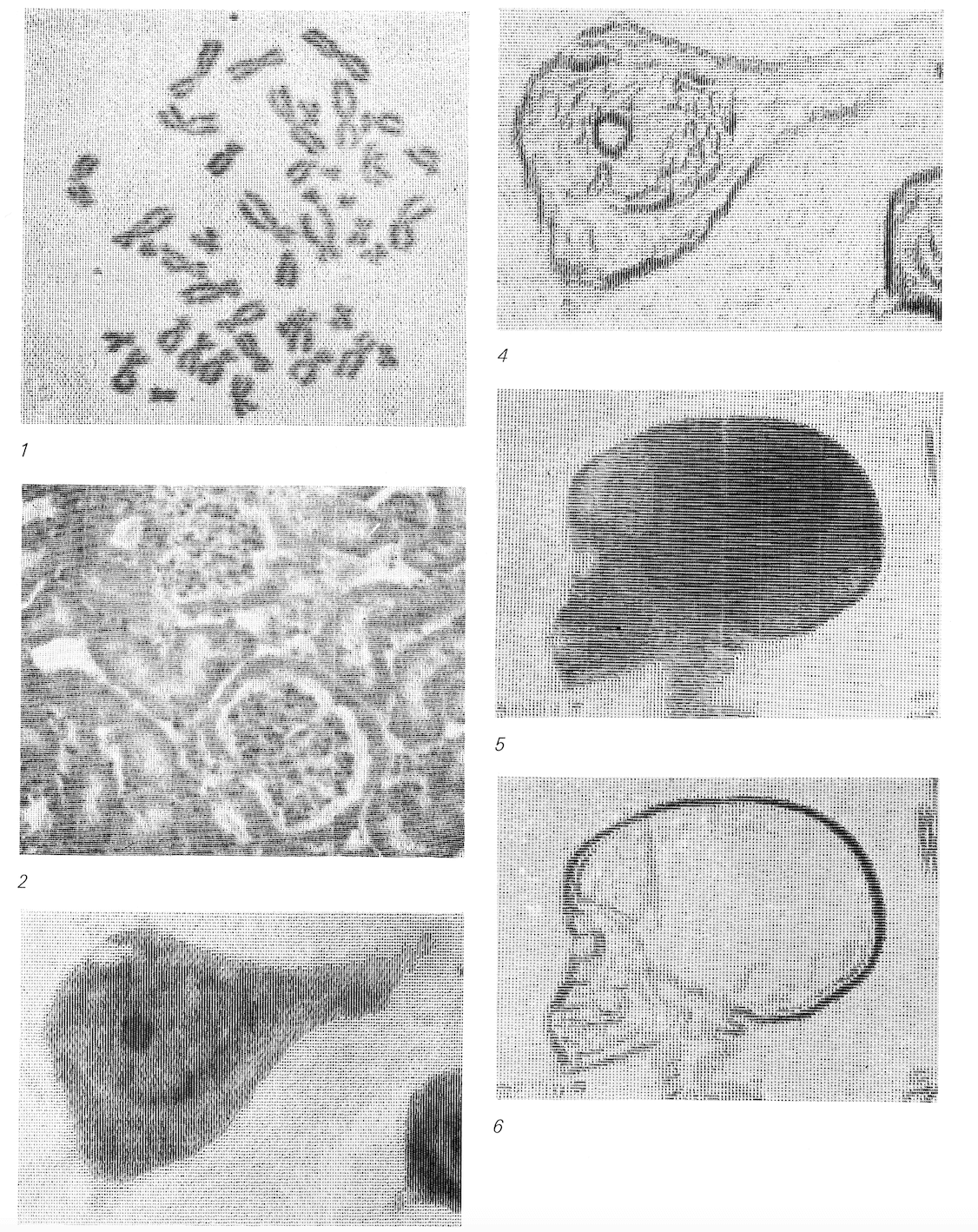

Judith Prewitt, instead took a visual approach and created a scientific image-processing system named Cydac. It converted microscopic images into data that a computer would analyze, for example, to differentiate types of cells. In the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition catalogue her work was described as follows:

“The image is scanned directly through a microscope and is divided into 40,000 minute elements. The light passing through each element is measured and recorded as a number. These numbers are analysed by a computer (IBM 7040) programmed to recognize different types of cells and other objects of medical and biological interest. The computer also generates pictorial representations of the original image, using combinations of letters and symbols to simulate different tones of grey, as is shown in these examples.”

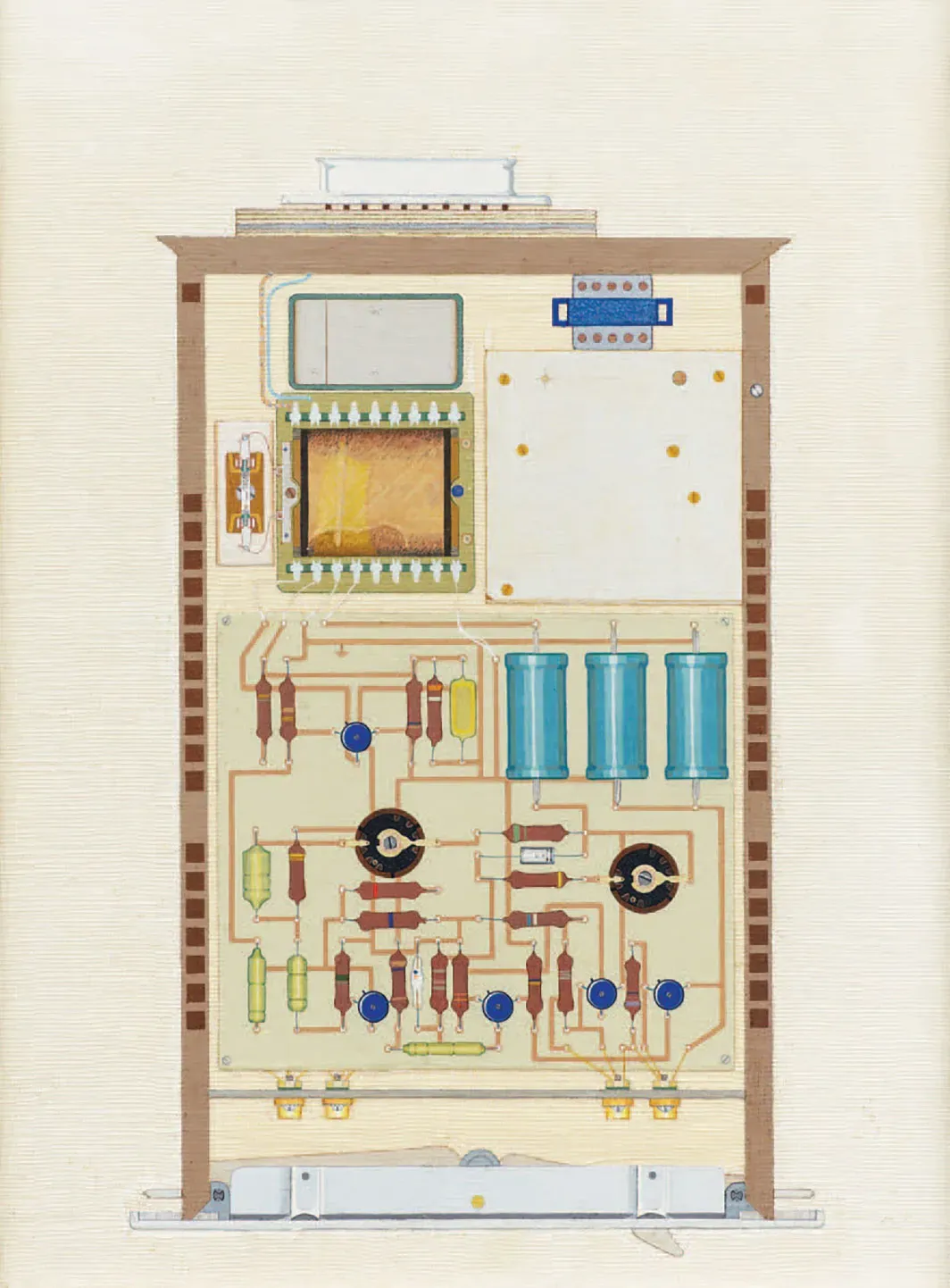

Ulla Wiggen: Painting the Hidden Systems of Computers

Meanwhile, Swedish artist Ulla Wiggen approached the machine itself as an art subject by painting computer components, from circuit boards to electrical pathways in great detail. Her pieces, such as Förstärkare (1964) and Kretsfamilj (1964), were inspired by cut-outs from computer magazines and parts of devices, which she arranged into unique compositions.

Early Computer Art Beyond Cybernetic Serendipity

Margit Rosen researched that between 1963 and 1969, over 50 exhibitions of computer-generated art took place globally. However, only two or three of these included female participants until 1967, and in two cases, the women themselves had organized the exhibitions. Worldwide, the total number of people experimenting with technologies and artistic mediums in computer art was no more than 200.

Before 1968, only a handful of female artists exhibited their work, among them Lillian Schwartz, Sue Hanauer, Linda Sue Lowery, Jane Moon, and Janice Lourie, who worked at IBM in the early 1960s. She developed a groundbreaking system that allowed designers to create woven patterns using a light pen, which earned her the IBM Invention Achievement Award and a feature in The New York Times. Lourie’s work was a milestone in what we now call computer-aided design.

Lillian Schwartz: Challenging Technology

One of the most prominent figures was Lillian Schwartz, who worked at Bell Labs for over 30 years as a resident visitor, a role similar to that of an artist in residence.

In 1970, she and her collaborator Ken Knowlton won first place in C&A’s Eighth Annual Computer Art Contest with Tapestry 𐌠, an image which was extracted from their computer-generated film Pixillation, created for American Telephone and Telegraph Co.

In her book “The Computer Artist’s Handbook” (1992) she wrote: “I had to push the early machine and cajole scientists to make the computer an art tool. Initially, I was satisfied when I pushed the machine into serving as a brush, an ink block, and oil paint. But the machine had to keep pace with me — just as I learned that I had to grow with the machine as its scientifically oriented powers evolved.”

On December 9, 2021 the Computer History Museum honored computer artist Lillian Schwartz for her pioneering work at the intersection of art and computing.

Women in Early Computer Art: An Incomplete Chapter

Little information exists about other female artists, such as Jane Moon. Rosen only found that her work was featured on the cover of Computers and Automation, a magazine published by computer scientist and accessible computing advocate Edmund C. Berkeley.

Similarly, there is limited information about Sue Hanauer. Like Schwartz, she worked at Bell Labs, programming much of the visual work attributed to Max Mathews and others, however, she was rarely credited.

As for Linda Sue Lowery, Rosen could only find that she was a graduate student in painting at George Washington University and that she won second prize in the CalComp plotter art competition during her university years.

“We do not know and will never know how many women may have explored aesthetic experiments with these machines, how many engaged in creative work privately, without ever sharing or preserving their results – perhaps because they felt it was not legitimate, or not worth showing. As historians, we always work with incomplete archives. The documents and traces we uncover tell contingent stories – shaped not only by what was preserved, but also by what was overlooked, neglected, or deliberately discarded.”

“When examining the role of women in early computer art, one must also begin with the question of access: Who had the opportunity to work with computers, and under what conditions could the necessary skills be acquired?", she notes.

“Women were involved in these fields, especially in roles like data entry, programming, and running systems. But it's important to point out that the number of women working in computing during the 1960s was actually much smaller than some popular stories suggest.”

In the 1960s, computers were not readily accessible, especially outside institutional or industrial contexts. Computing centers—whether military, governmental, or corporate—were highly regulated environments, and access to hardware and programming tools was often shaped by hierarchical and gendered structures.”

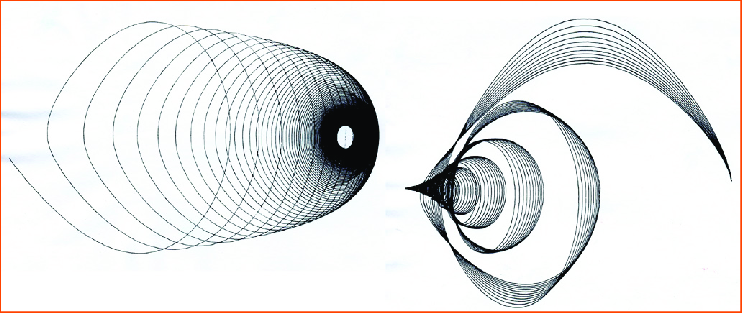

Inge Borchardt: Pioneering Analogue Computer Art

Rosen further adds that today, a common misunderstanding is to associate computer art exclusively with digital computers. “During the formative decades of computer-based art, analogue and hybrid computing technologies also played a significant role. The history of early computer art is far more technologically diverse than the term might suggest,” she explains.

Inge Borchardt is the perfect example of this, who in 1966, presented analog computer-based works at the Laeiszhalle in Hamburg. The artist, who worked at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY), where she led the analogue computer centre, used the EAI 231R analogue computer to produce drawings that were visual expressions of mathematical processes, art created by interpreting abstract mathematical models visually.

“Analog computers were much faster than digital ones at the time and mostly used in aerospace and engineering. Borchardt’s work reminds us that “computer art” did not start with digital technology alone,” says Rosen.

Interestingly, the 1960s also saw widespread fears that machines might eventually take over the creative process. Back then, people were worried that computers would replace human artists, just like they were expected to replace other jobs.

At the time, as Rosen points out, it was not so much the artists themselves as journalists and commentators who dramatized the idea that computers would ultimately replace human creators, just as they were expected to replace accountants or clerks. The artist, it was claimed, would become yet another casualty of automation.

“Back then, this was largely an abstract concern, as the computer had little real impact on creative labour. The fear, however, has endured until today – though comparisons with the 1960s must be drawn with care”, she says . “The current scale, speed, and corporate logic of automation – especially when entangled with AI – represent not a simple continuation, but a fundamental shift in the conditions under which images, texts, and sound reproduced, particularly in the field of applied art.

What persists is a dialectic that has accompanied computer art from the beginning: artists responding not in retreat, but by turning toward the very technologies that unsettled them – treating them not as threats, but as tools for reflection and resistance.”