How will COVID-19 affect the efforts on social and environmental issues within the industry? What role does the circular economy play and where lie the chances and barriers for change? Facts, figures, and expert opinions.

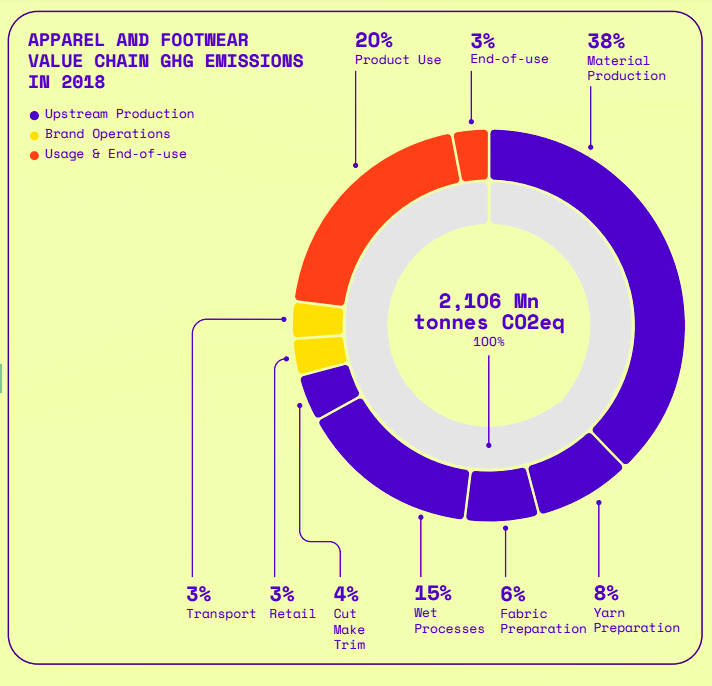

The global pandemic has exposed how vulnerable the conventional fashion system is. During the year 2020, many brands and retailers filed for bankruptcy. Among them, Neiman Marcus Group, DVF Studio U.K., J.C. Penney, John Varvatos, ALDO Group, or True Religion to name just a few. How will fashion, one of the biggest industries in the world, generating $2.5 trillion in global annual revenues before the pandemic, respond to the disruption and what effect could it have on sustainability efforts? Will they stall or accelerate? New reports show that consumers are more conscious about their shopping habits and the Black Lives Matter movement has increased the pressure to solve social issues such as systemic racism that also intersects with the fashion industry. The State of Fashion Coronavirus Update report by McKinsey states: “Once the dust settles on the immediate crisis, fashion will face a recessionary market and an industry landscape still undergoing a dramatic transformation. Indeed, consumer pessimism about the economy is widespread, with 75% of shoppers in Europe and the United States believing that their financial situation will be affected negatively for more than two months. Some experts say that consumer sentiment may never recover to pre-2020 levels as anti-consumerism and economic fallout cast a shadow over global markets and shoppers are hit hard by a global recession.”

Despite consumers who most likely will be more cost-conscious in the future, according to a survey conducted in Germany and the UK from April 2020, two-thirds say it has become even more important to limit climate change following COVID-19. They are also willing to change their consumption habits as 60% report spending less on fashion during the crisis, and approximately half expect that trend to continue after the crisis passes. However, consumers are likely to cut back on accessories, jewelry, and other discretionary categories before reducing their spending on apparel and footwear.

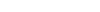

Renowned trend forecaster Li Edelkoort comments on the crisis as an awakening of consciousness: “The virus can be seen as a representation of our conscience… it brings to light what is so terribly wrong with society and every day that becomes more clear. It teaches us to slow down and to change our ways.” But where to start? As the fashion industry suffers from a rising trust deficit, one important pillar to affect change is transparency. But in contrast to the self-confident PR slogans that promote sustainable fashion collections, many companies are rather reserved when it comes to concrete facts and figures on sustainability efforts. The “Fashion Transparency Index 2020” surveyed 250 companies about their measures regarding social and environmental standards. H&M came first on the scale with a transparency rate of 73%, followed by C&A at 70%, Adidas and Reebok at 69%, and Esprit at 64%. More than half (54%) of brands score 20% or less. However, there are fewer low-scoring brands compared to the year before. 28% of brands reach 10% or less, compared to 36% of brands last year.

The report states: “As in previous editions of the Index, brands disclose more about their policies than they do about how they put those policies into action. Brands disclose comparatively less about the outcomes, results, and progress they have made to address social and environmental issues in the business and across the supply chain.” The overall average score among brands in the Policy and Commitments section is 52% while all other sections’ average scores are less than 30%. The good news is that brands are publishing more policies than they were in previous years (52% section average score in 2020, compared to 48% in 2019), but brands continue to lack transparency when it comes to the types of information that enables external stakeholders to hold them to account, e.g. detailed supplier lists, audit results, wage data, or climate impact.

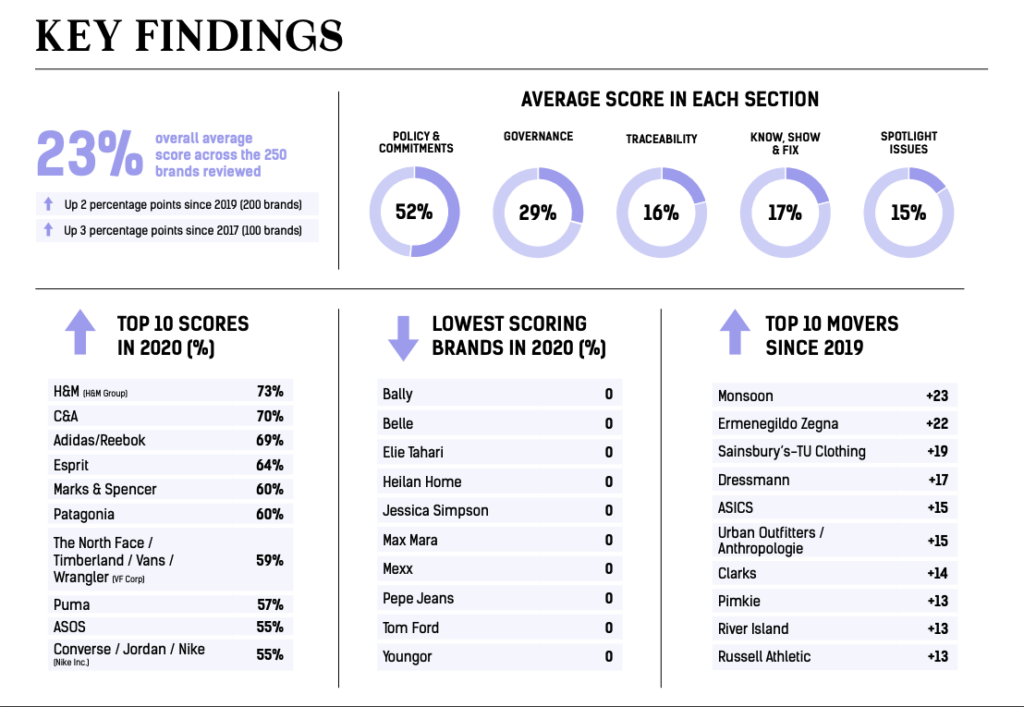

The industry’s environmental footprint is enormous. McKinsey’s recent research shows that the sector was responsible for some 2.1 billion metric tons of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2018, about 4% of the global total. To set that in context, the fashion industry emits about the same quantity of GHGs per year as the entire economies of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom combined. The 2020 report “Fashion on Climate” by McKinsey in collaboration with The Global Fashion Agenda further states: “When COVID-19 erupted this year, it highlighted the interconnectedness of our lives and the inherent uncertainty surrounding global economies, businesses, and humankind. Similarly, the protests associated with the Black Lives Matter movement have increased the pressure to solve social issues that pervade large parts of society and the fashion industry. This turbulent year has heightened awareness of the many challenges the fashion industry is facing, including in supplier relationships, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, employment structures, overproduction, and wastage.”

The report also highlights opportunities: Under an accelerated abatement scenario, the industry can reduce emissions to around 1.1 billion tonnes in 2030, putting it on the 1.5-degree pathway. This is achievable through the reduction of emissions from upstream operations, from brands’ own operations, and through the encouragement of sustainable consumer behaviors.

Reuse, Repair, Recycle: The Circular Economy

One of the great hopes leading to a more sustainable fashion industry is the circular economy, also known as “Cradle to Cradle”. It describes an economic system in which products do not end up in landfills at the end of their life but continue to live on as new goods. The concept distinguishes between a technical and a biological cycle. The product design already considers that the various components can be separated again in the recycling process.

The material must be wholly recyclable or returned to the biological cycle as a nutrient. Other than dismantle, produce, and dispose that describes our current linear model, the circular economy is all about reuse, repair, and recycle — two opposing concepts with different effects on resource consumption and environmental impacts.

In a circular economy, waste becomes a resource — a tempting idea, especially for the fast fashion industry. Discarded clothing, of which there are 11.9 million tons per year in the USA alone, could be transformed into new fashion trends. That would save resources and a lot of money. And it does not contradict economic goals; it supports them. But there is still a long way to go.

Today, the recycling rate of all materials in the textile industry worldwide is only 13 percent. Less than one percent is used to make new garments. Most old clothes are shredded and processed into rags, insulating materials, or fillers. The so-called fiber-to-fiber recycling, which spins new yarn from old apparel, is reaching its technological limits because shirts, dresses, and trousers consist of different fiber blends. “A piece of clothing is partly made of elastane, cotton, and polyester,” explains Daniel Bücher, researcher in textile engineering at the Institute of Textile Technology (ITA) at RWTH Aachen University in Germany.

“Separating these material mixes is extremely difficult and expensive. One possibility would be to produce clothing using only one material. However, this would be at the expense of wearing comfort, aesthetics, variety, and ease of care. In the end, fashion companies would not be able to recycle clothing endlessly, as every recycling process reduces the quality of the fibers. Sooner or later, they have to add new raw materials.”

Another challenge is that collecting and recycling discarded clothing would still consume large amounts of energy. Supporters of the circular economy, therefore, rely on a breakthrough in the field of renewables. Francesco La Camera, head of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), is optimistic: “By the year 2050, 86 percent of the world’s electricity could come from green sources”, he says. But he also warned that the expansion of renewables must accelerate massively. The installation of wind and solar energy has to take place six times faster than before.

Today, the circular economy still has its technological limits, but a C2C principle is also an important approach that can make a crucial contribution to sustainability in the future. “But to solve the numerous challenges of a highly globalized industry with non-transparent supply chains such as the fashion industry, we need more complex solutions,” says Bücher.

Textiles account for 15 percent of global plastic production.

A company that takes sustainability seriously must change its business model and implement sustainability strategies along the entire value chain. The Global Fashion Agenda identifies eight priorities, including supply chain transparency, responsible use of resources and chemicals, fair working conditions, and the use of material mixes that are easier to recycle or biodegradable. “That also includes finding an alternative to the petroleum-based synthetic fiber polyester,” says Bücher. “During each washing, our clothing releases small fibers, which then enter rivers and oceans as microplastics via the sewage system.”

According to the “Plastics Atlas 2019”, a study by the German Heinrich Böll Foundation, the textile industry processed about half of all polyester fibers produced worldwide in clothing in 2017. Textiles, industrial ones included, account for 15 percent of the global plastic production.

“Polyester is so popular in the textile industry because it’s very cheap to produce. The production of synthetic fibers is much easier and faster than that of natural fibers, which first have to grow and then to be harvested and processed,” explains Bücher. “Synthetic fibers consist of polymers that serve as the main component for the production of plastics. They are melted down, spun out, stretched, and processed into a yarn. We could return to wool, cotton, silk, and linen as the most important materials for clothing, but then we would need enormous landmass and even more amounts of water.”

An alternative, according to Bücher, could be biodegradable synthetic fibers. Unlike plastic, its production doesn’t require the use of fossil fuels. It would be the best option because it combats the cause of the plastic fiber problem. To make the promising approaches from the laboratory marketable, however, there is still a great need for investment in research and development. “The textile industry would also have to work more closely together and share its research results, to establishing new technologies much quicker,” said Bücher.

Sustainable Fashion means rethinking our Relationship with Clothes

For Stefan Schaltegger, economist and professor of sustainability management at Leuphana University in Lüneburg, Germany, technocratic approaches alone are not enough. “We also have to change the way we consume fashion. Slow fashion, in combination with innovation, is more promising. Anything that extends the lifespan of a garment makes more ecological sense than maintaining the fast fashion model and only reducing its impact through recycling.”

To stop the disposable culture of fashion, we have to rethink our relationship with the clothes we wear. Or, as Li Edelkoort put it: “Garments are offered cheaper than a sandwich. Prices profess that these clothes are to be thrown away, discarded, and forgotten before being loved and savored, teaching young consumers that fashion has no value.”

Garments are offered cheaper than a sandwich. Prices profess that these clothes are to be thrown away, discarded, and forgotten before being loved and savored, teaching young consumers that fashion has no value.Li Edelkoort

To counter the fast-fashion approach, more and more business models have emerged that focus on the conscious consumption of clothing. The range extends from rental services and second-hand platforms to labels that exclusively sell timeless collections to repair services. The New York startup Denim Therapy extends the life of people’s favorite jeans by fixing holes and modernizing its design. Second-hand platform Vestiaire Collective offers high fashion for less, and the e-commerce platform Not Just A Label follows a slow fashion approach. It provides independent designers from 150 countries the opportunity to present their collections and sell them without intermediaries. Designer Misha Nonoo established an on-demand business model with manufacturing based in Peru and China. They only start sewing a garment after a customer places an order. McKinsey’s 2019 State of Fashion report stated that made-to-order production would become more popular in the fashion industry by 2025, because it would allow brands to reduce their overstock and to adapt more quickly to consumer demand. During the lockdown, consumers shifted to sweatpants and leisurewear, and Nonoo was able to adapt immediately. Instead, many fast-fashion chains got stuck with enormous piles of unsold clothes.

“The solutions mentioned, based on a combination of innovative technologies and new business models, describe the triad of efficiency, sufficiency, and consistency,” explains Schaltegger. Efficiency means “make more out of less,” focusing on productive use of matter and energy. Sufficiency represents changing our lifestyles to conserve resources and questioning our consumption habits. And the consistency strategy describes the harmonic coexistence of technology and nature according to the circular economy and its Cradle-to-Cradle approach. “In the end, only an intelligent combination of efficiency, sufficiency, and consistency strategies tailored to each company will lead to greater sustainability in the long term.”

Adapt or Die: A Darwinian moment for the Global Fashion Industry

The McKinsey report further predicts that “the pandemic will bring values around sustainability into sharp focus, intensifying discussions, and further polarising views around materialism, over-consumption, and irresponsible business practices.” Fashion companies have to reposition themselves and adapt as the pandemic will be a Darwinian moment for the global fashion industry. Innovating in all areas will be crucial to overcoming the crisis. In the meantime, sustainability credentials will be one method to regain consumers’ trust and wallets. However, predicts the report, “consumers hit hard by a global recession will be more cost-conscious than ever and may consider sustainability in their purchasing decisions even less than before. Whatever the outcome, sustainability messaging will need to be grounded in authentic behavior and rigorous internal practices.”