Barcelona closes its residential areas to car traffic, making room for the people. But do they really want that? We asked the inventor of the “superblocks”.

In the middle of an intersection in Barcelona’s Sant Antoni neighborhood, children kick a soccer ball, families picnic at wooden tables, and two seniors play a game of chess. Only now and then, a car rolls by.

Since 2018, Sant Antoni has been a “superblock,” also called “superilles” (super islands) in Catalan. Each island comprises 9 city blocks, combined into a traffic-calmed neighborhood that belongs only to the residents. A sophisticated system of one-way streets diverts traffic to the streets outside the superblock. Only residents, ambulances, and delivery vehicles can pass. Today, there are five superblocks in the city; in the future there could be 500. The plan is to reinvent urban space, making it more livable, greener, and healthier. That also means rethinking the role of the car in cities – the iconic symbol of the economic miracle. Slowly, over the 20th century, it has carved its way through our cities.

Barcelona: Too many cars, too little space

Barcelona is no exception. With 6,000 vehicles per square kilometer, the Catalan metropolis has the highest car density in the EU. Yet private cars account for only about 20% of all trips but occupy 60% of the space, mainly for parking. Commuters account for 85% of these car trips streaming into the city every morning from the suburbs. Barcelona consistently exceeds WHO limits for nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter. According to a city’s health department report, air pollution causes more than 350 premature deaths each year. The Barcelona Institute for Global Health study also links poor air quality to an increased risk of COVID-19 infection. In addition to bad air, noise is also a problem for the people of Barcelona. About 57% live in areas with higher levels of noise than recommended by the WHO. According to the city council, this is mainly due to motorized traffic.

Like Barcelona, almost all metropolises in the world suffer the same fate. Thousands have declared a climate emergency in recent years, including the Catalan capital in January 2020. Studies show that cities are responsible for 70% of all greenhouse gases and suffer particularly strongly from the consequences of climate change.

By 2050, 68% of the world’s population will live in cities. To turn these mega metropolises into places worth living in, we need solutions that rethink urban development and mobility – solutions like the “Superblocks”.

500 Superblocks for 300 million euros

“Our computer simulations show that we would only need to remove 15% of cars from Barcelona to reclaim 60% of public space,” explains Salvador Rueda, who is the father of the Superblocks.

We meet the Catalan urban planner in a small café in the Eixample district. He orders a cortado. Over 35 years, he has developed the superblock model in Barcelona, simulating and implementing the first neighborhoods. “To introduce 500 tactical superblocks throughout Barcelona, you would only need a budget of 300 million euros,” he explains. “That’s how much the new tunnel they built under Plaça Glòries cost. So this is not a cost issue. It’s a political issue and has to do with conflicts of interest,” he says energetically.

Before retiring, Rueda headed Barcelona’s Urban Ecology Agency for 20 years. Today, the 68-year-old advises cities worldwide that want to adapt the superblock model. These have included metropolises such as New York, Madrid, Montreal, Vancouver, Buenos Aires, Bogotá, and Berlin. Many recognize the benefits of the superblock model. With measures from tactical urbanism, which uses modular furniture, paint, and planters to quickly and effectively create change in public spaces, superblocks are implemented cost-effectively.

They don’t require the demolition of buildings, nor do they require extensive redevelopment. But the most important task of the Superblock model is to change mobility in the city. To tackle this challenge, cities need efficient public transportation combined with an extensive bicycle and pedestrian network.

Barcelona Superblock of Sant Antoni in the making

Cities as efficient as the human organism

Rueda describes livable cities of the future as “compact, complex, efficient and socially inclusive” ecosystems. Sounds complicated? But it’s quite simple: the superblock, measuring 400 by 400 meters, forms the compact base and functions within the metropolis like a small city in its own right. To fill this place with life, it needs organizational diversity such as stores, markets, museums, hospitals, universities, and green spaces – this is what Rueda means by “complex.” Thanks to the short distances, residents in the superblock can reach everything on foot, by bike or by public transport in just a few minutes. Each superblock also manages its resources efficiently and uses energy, water, and materials according to the principle of a circular economy.

The information society creates new wealth through knowledge, digital products replace physical ones, and the economy dematerializes, Rueda describes a possible future scenario. The fourth principle of a livable city is social cohesion, fostered by public places. Rueda compares these places to the agora in ancient Greece, which served as the central meeting place for all of Athens. Here, residents met to debate, settle matters of state or watch performers.

Cities as compact and complex ecosystems

“Cities today are poorly organized,” Rueda says. A city, he says, must function similarly to a compact and complex ecosystem in nature, like a coral reef. “Life on Earth has also continued to evolve and increase in complexity throughout evolutionary history – from single-celled organisms to humans,” he continues. “Today, our brain is the most complex system we know. It’s an organ capable of learning, has consciousness and controls all the processes in our body. Yet the human body requires just as much energy as a 150-watt light bulb. The fact that the body manages so much complexity with so little energy fascinates me. Cities can learn something from this principle.”

Densely populated Barcelona is the ideal starting point for the compact and livable city of the future. Instead, Rueda describes metropolises with sprawling suburbs as urban deserts devoid of life. For example, Vancouver has only a tiny center surrounded by a 200-kilometer-wide metropolitan region crammed with single-family homes. “These distances are too great to introduce an efficient public transportation network. This no longer has anything to do with cities.” The goal, he said, must be to transform these “suburbias” into cities of their own that function according to the principles mentioned above. “Each city is unique. The urban model with the four components serves as a theoretical basis to examine the complex realities of each city individually, and the superblocks provide the framework.”

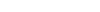

Why is Barcelona build in squares? Catalan engineer and planner Ildefons Cerdà understood that an orthogonal street network was the most efficient way to organize a city.

Why is Barcelona build in squares?

The concept of the superblocks dates back to the spirit of a visionary urban development project from the mid-19th century. At that time, Barcelona commissioned Catalan engineer and planner Ildefons Cerdà to create space for its rapidly growing population. Thousands of people flocked to the city from the countryside during industrialization to work in the newly built factories. They lived cramped and in poor hygienic conditions behind Barcelona’s city walls, and countless fell ill and died of cholera. Cerdà had the city wall demolished and paved the way for modern Barcelona with the new city “Eixample” (Catalan for “extension”), a planned city with a square street grid, which visitors today send to friends and family as a postcard motif.

For each block of houses, Cerdà planned green, publicly accessible courtyards that would extend in all directions. To do this, he precisely calculated the width and height of the blocks to ensure optimal lighting and ventilation conditions. But Cerdà was never able to implement his progressive plan fully, many ridiculed his ideas, and the concept eventually failed for political reasons. More than 160 years later, Barcelona’s housing blocks have grown skyward; instead of green parks, there are built-up courtyards, all privately owned. “The superblock model is Cerdà’s plan translated into the 21st century,” Rueda says. “Cerdà understood at the time that an orthogonal street network was the most efficient way to organize a city.”

Cerdà’s plan can be considered as the beginning go the Barcelona Superblock project.

Olympia and the Barcelona Superblock Project

In the late 1980s, Barcelona began preparations for the 1992 Olympics on a grand scale, and Rueda was the environmental engineer in charge of the city. “At that time, the main focus was on transforming public space, enlarging sidewalks, and creating gardens in abandoned housing estates and warehouses,” he explains. “Sustainability and particulate pollution didn’t matter as much back then; people were more concerned about the health effects of car noise.” The city hired Rueda to develop a solution to reduce noise levels to the internationally recommended 65 decibels.

Rueda found that the biggest source of noise was through traffic in residential neighborhoods. So he found an efficient solution to divert vehicles away from the residential neighborhoods – the idea for the Superblocks was born. It took another six years before the city finally gave the go-ahead for the first superblock in the Born neighborhood of the old city in 1993, followed by two more in the Vila de Gracia neighborhood in 2000. Then it became quiet about the superblocks until Mayor Ada Colau revived the model and made it a central part of the city’s new mobility plan. In 2016, the municipal government introduced another super island in the Poblenou neighborhood.

Superblock Poblenou – a project that polarizes

Silvia Casorrán is deputy chief architect and mobility advisor at Barcelona City Council. She lives in Superblock Poblenou and remembers the beginnings well. “Some people from the neighborhood were unsure about the impact the superblock would have on their daily life, store owners feared a loss of sales,” she says. The controversy was so immense that two citizens’ initiatives were formed, one for the Superblocks and the other against it. Discussions went on for months.

Communication on the part of the city to prepare residents for the change was very scarce at the time. Lessons were learned: “For the subsequent superblock in Sant Antoni, the city council developed a comprehensive action plan and involved the neighborhood, schools, and trade associations. The population received this very well,” explains Dani Alsina, the city’s technical coordinator responsible for the Superblock project.

Today, most of the Superblock skeptics from Poblenou have changed sides. And the consequences feared by the shopkeepers have also failed to materialize. “The number of local stores increased by about 30% thanks to the new walk-in customers,” Alsina says. New places of exchange also emerged. “Before there were no places where the neighborhood could meet, many didn’t even know each other,” says architect Casorrán. “Today, we celebrate birthdays together in the superblock, arrange to meet in a Whatsapp group. A community has been created. When public space becomes available to people, they use it.”

“Ejes Verdes” – green axes for the Eixample

There will soon be more space for residents in the Eixample district. The redesign of 4 major streets will begin in summer 2022, which gradually evolves into green axes.

To redesign the traffic-calmed streets, the city announced an ideas competition, which also called for solutions for the resource-saving maintenance of the facilities. The architectural studio Cierto won the competition for the street Consell de Cent. Carlota de Gispert Sampera, one of the architects in charge, rolls out the project plan and explains, “The green squares will be equipped with a sustainable urban drainage system to efficiently use rainwater and close the water cycle. We’re also putting in structured soil, a mixture of coarse-grained gravel and mineral components so that the roots have room and are better supplied with water and nutrients.”

Studio Cierto also ensured that the trees and plants got the correct location. “In Consell de Cent street, the mountainside has much more light, so the trees are planted there, so they can grow faster. The trees also provide more shade for people during the hot summer months. In the cold season, they lose their leaves and give way to light and warmth for the residents,” she continues.

So far, there are only two instead of the recommended 10 square meters of green space per inhabitant in the Eixample district. According to the city council, the green places there are to increase 10-fold, from 1% to an average of 14%. In total, 21 new green places will be created by 2030. And when is a new superblock in the style of Sant Antoni and Poblenou planned? There is no specific date yet, but they continue to play an important role in the current local government’s urban planning.

On a small scale, super islands have already shown that they can improve people’s quality of life on a large scope. But superblocks would have to be built across the entire city to reach their full potential. That’s unsettling to some people. That’s why every project that involves Barcelona’s citizens in the design of their town and further promotes the acceptance of superblocks is a small step in the right direction – on the way to livable, green, and healthy cities of tomorrow.

This article was first published in Perspective Daily, Germany’s digital magazine for constructive journalism.