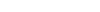

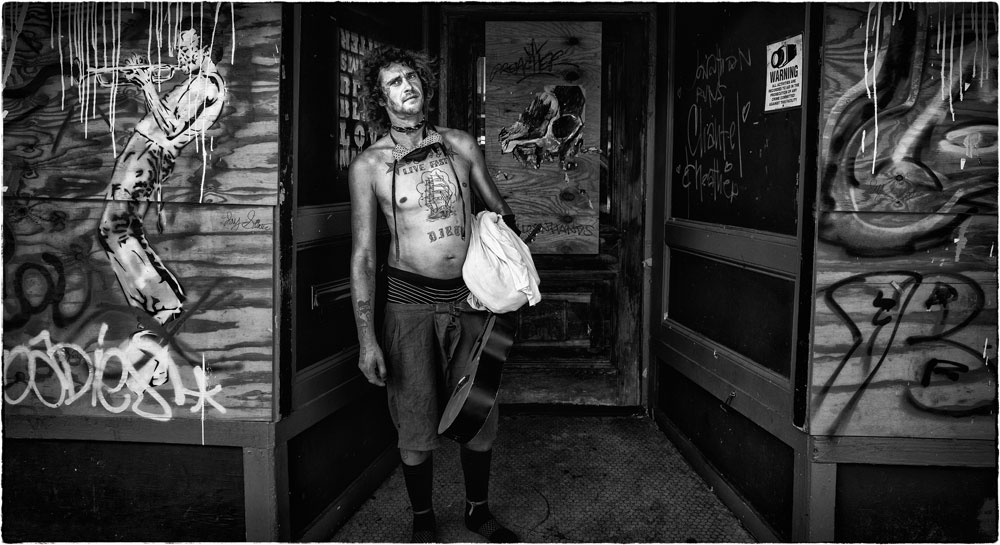

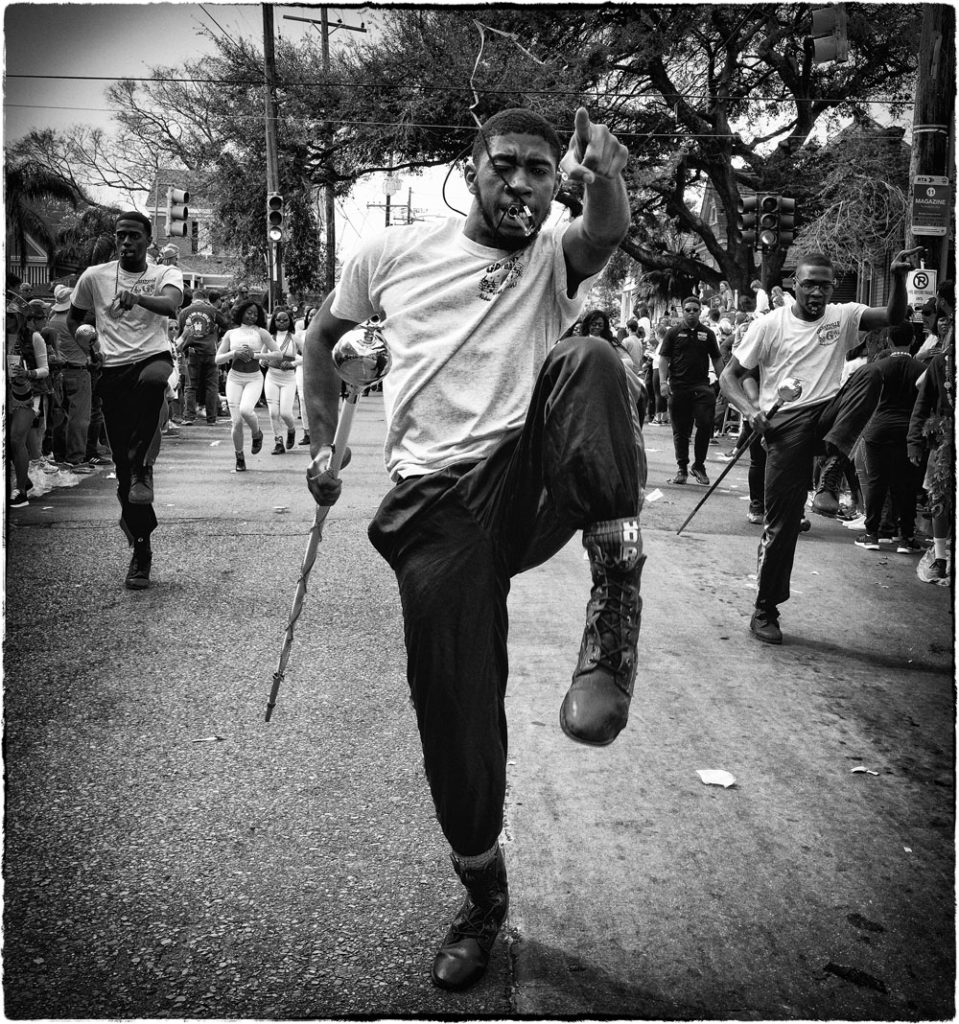

The director, producer, and photographer James Hayman shows scenes from the daily life of New Orleans in intimate black-and-white imagery. He describes the city as a place with a very particular “joie de vivre,” cultural pride, and a strong sense of community.

“When I first moved here to run the television show NCIS: New Orleans, the place’s individuality struck me. I think it’s the most atypical of U.S. cities, feeling more like an amalgam of European and Caribbean towns. As it happens for me whenever I am in a new place, this opens my creative eye. My unfamiliarity and subsequent fascination with New Orleans were directly connected with photographing the city. Working on the show gave me access to parts of it I might not have had otherwise.

There is a very particular “joie de vivre” in New Orleans. Not only do people embrace celebrations, food, music, and the Saints, but, more importantly, there is a civic and cultural pride here. There is a sense of being the underdog and always rising above what catastrophes life throws at you. That is accomplished by everyone helping each other. There is a strong sense of shared community.

Not only do people embrace celebrations, food, music, and the Saints, but, more importantly, there is a civic and cultural pride in New Orleans.

The flambeaux tradition dates back to 1857, during the first Mardi Gras. Wooden torches wrapped in rags were lit and used to guide parade routes during the night. The tradition continues into the present day with gas-powered torches used during the evening Mardi Gras parades. The crowd sees these standard-bearers as heroes who carry on a time-honored tradition and light our way through our celebrations.

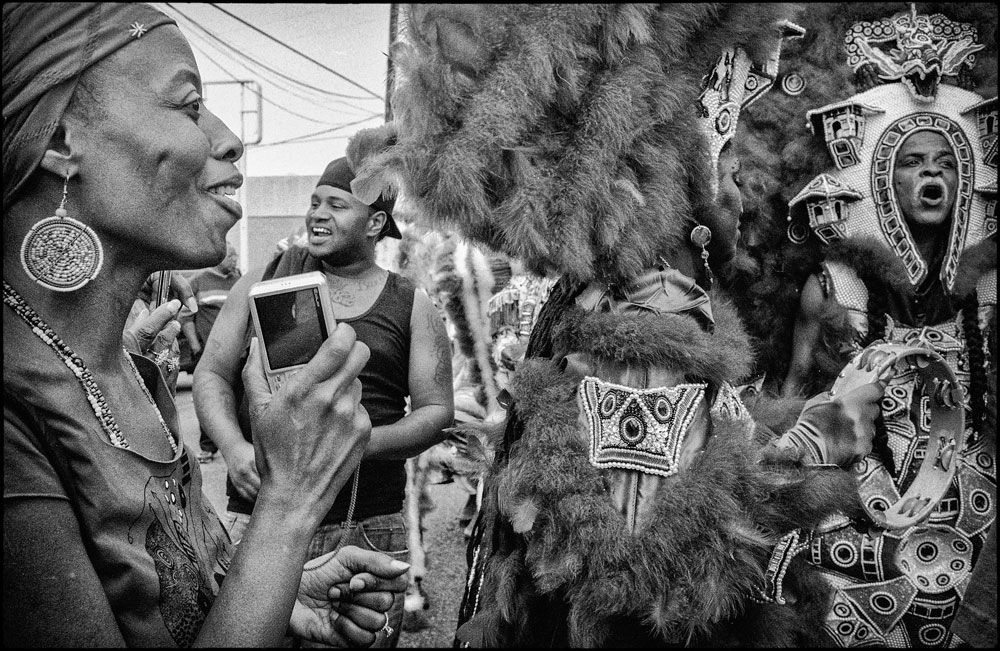

New Orleans welcomed me with open arms, and in doing so, revealed its many needs. It felt only right to give back, not just there but wherever I can. I believe it’s important to bring visibility to those in need, especially those living on what we might call the societal fringes. Yet, merely photographing them can feel exploitative. Therefore, by also supporting charity organizations, I aim to ensure the photos serve a purpose for the community. They challenge us to engage, to do more than just look.

That’s why I decided to do social work. First, I read an article about a man in the Lower Ninth Ward who had turned his grocery store into a food bank for his customers when the pandemic hit. I searched him out and started helping him financially. Second, my assistant from the show, Mary Thornton, started a nonprofit called Pack Essentials, which provides necessary items to those living on the street. I assist in distribution as well as financially. I am most proud of All Are One, a fund my wife Annie Potts, two friends of ours, and myself started. It gives cash payments to people in need. We have raised and distributed $120,000 in Los Angeles, Northern California, South Carolina, and Washington D.C. Currently, we are in the process of creating a distribution center in New Orleans as well.

In the spring of 2020, the city had a huge spike in COVID-19 cases, and the entire town shut down. I canceled my show on March 12. Many lost their work and needed assistance. While there was an overall sense of nervousness to interact, there was an overwhelming push to take care of those less fortunate. People embraced all the protocols, shuttered all communal spaces, and reached out to neighbors, friends, and the underprivileged to lend a helping hand.

I talk to my subjects before I press the shutter. I think it comes out of a very southern attitude.

When I first moved to New Orleans, I was warned not to ask someone how they were unless I had 15 or 20 minutes to spare because they were actually going to tell you.

My photographic process has changed during my time in New Orleans. My street photography used to be more surreptitious, keeping myself invisible while I captured moments. Now my approach has developed into a more interactive process. I talk to my subjects before I press the shutter. I think it comes out of a very southern attitude. When I first moved to New Orleans, I was warned not to ask someone how they were unless I had 15 or 20 minutes to spare because they were actually going to tell you. Coming from New York and Los Angeles, that was unknown to me. Now I have become one of those people!

I realize that the people’s stories all have an interest to me and allow my photography to capture a more telling narrative of who my subjects are. It also broadens me as a person, not just as a photographer. Understanding someone’s world, their perspective, can only expand mine as well.

Music in New Orleans is a true focal point of the culture. And just as the cultures and people here are such a mixture of various groups, music is the same. I’m a big music lover out of the 60s, so the local music calls to me. Also, everyone in this town plays an instrument. And all are heralded. So high school marching bands, corner brass bands, street buskers, club bands, right up to internationally known musicians all are somewhat on equal ground here.

My photo of the musician Dr. John came out of his being on our show. I met him through a series of friends in town, a very New Orleans trend, and then asked him to be on the show. That started a four-year friendship with him that unfortunately ended when he passed two years ago.

When a parade comes by in life, you need to take a moment to enjoy it. That is the epitome of New Orleans to me.

The first time I directed on the French Quarter’s streets, we were racing the light to finish a scene when a marching band and a second line passed. I watched my entire crew stop working and join the dancing in the streets. So we danced, the parade passed, we returned to work and finished our day. I realized that when a parade comes by in life, you need to take a moment to enjoy it. That is the epitome of New Orleans to me. Laissez les bons temps Rouler!”