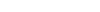

British photographer Rachael Talibart captures the moods of the ocean. While her critically acclaimed series “Sirens” portrays the wild temper of the water, her work “Ghosts in the Shell” speaks to the gentler spirit of the sea.

“Making Ghost in the Shell has been so relaxing! As I stroll along the shore on the South Coast of England, I’m on the lookout for interesting subjects. I also feel a heightened awareness brought to me by my senses, the light on the water, the rhythm of the waves, the taste of salt in the air, the breeze on my skin. I feel I connect more deeply with the environment and forget about everything else going on in the world. I like to take things slowly – it’s not unusual for me to spend an entire day on the beach from dawn to dusk. Sometimes, I walk a long way, not realising how far I’ve gone because I’ve lost track of time and distance. Other times, I stay in just one small area, discovering more by looking harder.

“The chalk fragments are by far the oldest shells in my series. Incredibly, they contain shells of creatures alive as much as 145 million years ago.”

Chalk is the dominant rock on the South Coast of England, where I grew up and still make most of my photographs. It was very much part of my childhood. There was chalk in our garden soil, chalky sediment suspended in the sea, lumps of chalk to play with on the beach, and, of course, the mighty chalk cliffs of the Seven Sisters. I included fragments of chalk in “Ghost in the Shell” because chalk consists of the shells of tiny marine creatures and the calcareous remains of algae. Most of it was deposited during the Cretaceous period. (‘Creta’ comes from the Latin word for chalk.) So the chalk fragments are ancient, by far the oldest shells in my series. Humanity is about 300,000 years old. Incredibly, these chalk fragments contain shells of creatures alive as much as 145 million years ago.

It seems strange to realise that I actually started to work on “Ghost in the Shell” before I began with “Sirens.” These photographs are attention grabbers in the tradition of the ‘sublime,’ images of big Nature that create ‘shock’ and ‘awe.’ The Ghost in the Shell photographs appear gentler. They won’t have the same immediate impact, but I hope they provoke a thoughtful response. People sometimes ask me whether it’s limiting, choosing to work only at the coast. I find the sea has so many moods that there’s always something different to do, and the variety keeps me going. My Sirens series is about the sea in turmoil, whereas Ghost in the Shell reflects a calmer feeling. However, I need sea foam at the shoreline to create the ghostly movement around the shells and foam whisks up during storms. So, stormy days matter for both portfolios. The greatest challenge to capture the shells is Patience! Generally, it has never been my strong suit in life, but I seem to have found some stores of it for this project. Encountering a nice shell is just the first step. I also need the sea to do something interesting around it. Often, I will set up with a shell, and the sea never touches it. Or, the ocean carries it up the beach, and all I capture is a white rectangle of moving foam. On one memorable occasion, a dog picked up my shell and carried it away, just at the crucial moment!

“Once the molluscs have left, there’s just a perfectly formed object that appears to have an almost entirely aesthetic function. Irresistible inspiration for artists!” – Rachael Talibart

“There is so much variety in shells. I think it’s safe to say that every single one is unique, like fingerprints or snowflakes” – Rachael Talibart

The ones scattered on the shore are usually empty. They’re pretty little treasures, Nature’s jewels, and I remember collecting and marveling over them as a child. I suspect shells may have been some of the earliest forms of jewelry and even currency in certain communities. Once the molluscs have left, there’s just the shell, a perfectly formed object that appears to have an almost entirely aesthetic function. Irresistible inspiration for artists! Even empty shells have a purpose in the natural world, and I always return them to the sea after I have finished photographing them. It’s easy to forget that they are, in fact, the remains of living creatures, creatures that are an integral part of the ocean ecology. In this series, I wanted to contrast the inanimate shells with the movement of sea foam as a ghostly echo of the life the shells once housed. Even if it’s not apparent on the surface, much of my work is influenced by my concern about the ecological crisis we face. Ghost in the Shell asks questions about time, absence, and change. I want to create beautiful pictures, but I also hope that these photographs will encourage people to look more closely and think a little more about things in Nature we might otherwise take for granted.

“Piddocks, also known as angel wings, are bioluminescent and glow in the dark. They use the serrated edges of their shells to grind away at clay, wood, or even soft rock to make burrows” – Rachael Talibart

There is so much variety in shells. They come in different shapes, of course, but also colours. You might think that one creature would always have a shell of a particular colour, but it is not so. Tellin shells, just as an example, can be white, pink, yellow, or purple. I think it’s safe to say that every single one is unique, like fingerprints or snowflakes. That’s an enticing concept. Probably the most exciting one I’ve photographed so far is the piddock. They are also known as Angel Wings for apparent reasons. Piddocks use the serrated edges of their shells to grind away at clay, wood, or even soft rock to make burrows. They do this by rotating. These burrows can be surprisingly deep. The piddock stays in its shelter for its whole life, eight years or so, using a siphon to suck in water that it then filters for nutrients. After a piddock dies, other sea creatures then use its cave.

Piddocks glow in the dark! I have yet to see this phenomenon for myself, but I understand that they are bioluminescent and glow blue-green around their edges. The protein that creates the piddock’s glow has been used to identify when people are becoming ill as it gives off light when it meets chemicals produced by white blood cells to fight infections. This can help diagnose infections at an early stage, improving outcomes. Isn’t Nature marvelous?”

You’ll also find Rachael Talibart on Instagram via @rachaeltalibart and Twitter at @rtalibart