When was the last time you enjoyed a great piece of art? Maybe you were in a museum, closely observing every brushstroke of a painting. Or it was a movie, the kind that leaves you sunk in your seat while the credits roll, the story still resonating in your mind.

Have you ever wondered: Why does music move us to tears? And what happens when we lose ourselves in the creative process?

Aesthetic experiences, as Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross write in their book Your Brain on Art, “trigger the release of neurochemicals, hormones, and endorphins that offer you an emotional release.”

We all intuitively feel that the arts matter. But why do we know so little about how they impact us? Couldn’t we leverage the benefits of the arts even more if we had a better scientific understanding how our brains and bodies respond to aesthetic experiences?

Neuroaesthetics, an emerging field of research at the intersection of art and science, tries to find answers to these questions by combining behavioural studies with brain research.

Neuroaesthetics: “The Question is the question”

“What are the benefits of bringing the brain into studying aesthetic experiences? I think that’s a valid question, because behavioral studies often already offer a lot of insights,” explains Dr. Anjan Chatterjee, professor of neurology, psychology, and architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, in an interview with The Overview. A pioneer in the field, he founded the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, the world's first lab dedicated to exploring the brain’s reactions to aesthetic experiences.

"The brain helps us see our responses to aesthetic experiences in new ways," he explains. "It also lets us understand the systems and biological principles by which our brains developed. This gives us a clearer idea of how to ask the right questions. Brain imaging can also inform us about how we might be responding to objects and stimuli in the world in a way that we're not even aware of.”

A mantra in Chatterjee’s lab is: “The Question is the question.” And to find the right one, he and his team take a multidisciplinary approach, including behavioral studies and philosophical perspectives on aesthetics, in addition to the biology of the brain, before starting a research project and collecting neural data.

“Beauty is in the brain of the beholder”

Before we dive deeper into the questions neuroaesthetics seeks to answer, it’s important to take a closer look at the meaning of beauty. “We first have to ask ourselves: Beauty of what? There are differences between our aesthetic responses to human-made artifacts and nature.”

Studies have found that we respond to natural beauty in very similar ways, no matter where in the world we live. For example, we tend to find the same people attractive. This also applies to natural landscapes, like a sunset on the horizon of the ocean or a mountain panorama. "I always say, ‘Beauty is in the brain of the beholder.’ And our brains are more similar than they are different,” Chatterjee explains.

He notes that over millennia, when we lived out in the savanna, our brains evolved in similar ways, so we respond to nature more consistently across cultures. However, when it comes to cultural artifacts—like architecture and art—people's reactions are far more varied, as culture in this form has only existed for about 45,000 years, with the earliest paintings found in Indonesia at the Leang Timpuseng Cave, depicting hands and images of pigs and buffalos.

Given the personal preferences of aesthetic experiences with art, is it even possible to scientifically study them? Chatterjee explains that while preferences in art are indeed subjective, the underlying principles in how our brains process these responses are similar. So, if one person likes abstract art and another prefers figurative paintings, both have a similar reaction—just the trigger of that reaction is different. The underlying principles, this common ground, can be studied scientifically.

To help scientists structure their research, Chatterjee and his colleagues developed a framework of how aesthetic experiences emerge from the interplay of three large-scale brain systems:

- Sensory and Motor: This relates to how our senses perceive aesthetic objects and our motor responses, like appreciating the colors of a painting or how our body reacts and moves to music.

- Emotion-Valuation: This involves emotional reactions such as pleasure, awe, fear, joy, or frustration. Chatterjee adds that while early research in neuroaesthetics focused on pleasure, the field now explores the full range of aesthetic emotions.

- Knowledge and Meaning: This system processes our understanding and the meaning we ascribe to the artwork, influenced by our cultural background, experience, and education.

Think about watching a movie. The sensory system is responsible for how you perceive the visuals and sounds—the music building tension or the colors in the scenes. Your emotional system reacts to how those visuals and sounds make you feel, whether you’re moved by a dramatic scene or scared by suspense. And your knowledge system kicks in when you start understanding the deeper meaning of the story, like realizing how a character's journey mirrors your own life experiences.

Pleasure From Understanding: The Default Mode Network

This knowledge system is closely linked to the Default Mode Network (DMN). One of the leading scientists researching its role in aesthetic experiences is Edward Vessel, a cognitive and computational neuroscientist and Assistant Professor of Psychology at the City College of New York.

“The default mode network is a set of highly interconnected brain regions,” he explains in an interview with The Overview. “It’s what we used to call a task negative network, which means that it’s typically more active when a person’s brain is not engaged with the outside world but turned inwards, for example during self reflection, autobiographical memory, imaginative forward thinking, mind wandering or daydreaming.”

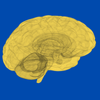

In a fMRI study, that uses scans to measure brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow, Vessel and his colleagues made a surprising discovery: They found the DMN activated when participants viewed highly aesthetically moving artworks, despite it usually being suppressed during externally-focused tasks.

“That was surprising because in other experiments in which participants were asked to listen to sounds and push buttons on a keyboard or look at images and respond to their content we would see that the visual system might be active and various attentional and executive control networks, but the default mode network was typically always suppressed.”

His findings suggest that the DMN is involved in processing meaning and self reflection when we have an intense aesthetic experience that moves us. “We seem to evaluate an artwork, a piece of music or the beauty of nature by what it means to us personally—how it relates to our sense of self and our life experiences.”

Learning Through Art: Curiosity, Creativity, and the Brain

According to Vessel, personalized aesthetic experiences can help us make sense of the world. “I think it shows that the arts are tapping into this mechanism for giving us pleasure from understanding. They engage our epistemic drive, our intrinsic motivation and curiosity. The arts could be a way to engage self-relevance and activate the DMN, helping us to connect more deeply with ideas and messages."

A few years ago, Vessel and his team conducted an experiment in the form of a writing workshop in which they showed participants either a prompt of three words or a visual artwork and asked to create a story based on it. One version of the experiment were artworks that someone had either rated very low or quite high for their aesthetic appeal.

When people were shown the artwork that resonated with them, they wrote longer stories and rated themselves as being more inspired. “I do think that there's a link between the mental states of being aesthetically moved and being creatively inspired”, explains Vessel. “The DMN seems to be a critical brain network for creativity, very involved in the brainstorming and generation of multiple ideas to solve a problem, what we also call divergent thinking.”

This could make art an ideal tool for fostering learning. That’s why Vessel and his team are also interested in thinking about ways to design curricula or teaching methods that integrate the arts and engage the student’s curiosity.

"El Sistema": How Music Powers the Brain

In Your Brain on Art, authors Ivy Ross, Chief Design Officer for Consumer Devices at Google, and Susan Magsamen, founder and Executive Director of the International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, introduce another example of how the arts can support learning, telling the story of Gustavo Dudamel, the musical director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Growing up in modest circumstances in Venezuela, at age 4, he joined El Sistema, a social program that teaches children to learn an instrument and play in an orchestral setting.

The project’s impact reaches far beyond music, as the children also develop cognitive, social, and emotional skills in the process. Research on comparable initiatives like the Miami Music Project also has shown that students become more competent, confident, caring, and connected, while also improving academically.

Dr. Assal Habibi, a neuroscientist at the Brain and Creativity Institute (BCI) at the University of Southern California, studied young musicians in the Youth Orchestra Los Angeles (YOLA) and discovered that music training changes brain structure. She found that it strengthens the brain networks involved in decision-making, revealing that music accelerates brain development in areas that process sound, develop language, perceive speech, and build reading skills.

Healing Through Art

Just as the arts can help us learn, they can also help us heal. Art therapy has been shown to be especially beneficial in cases of post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS). Chatterjee and his team at the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics are working with the Walter Reed Military Medical Center to investigate the effects art therapy has on veterans.

The patients participate in an eight-week therapy program, where at the beginning, they are given a blank paper mask to paint, an exercise that serves as a form of self-portraiture. They also can participate in a study that examines changes in the brain through advanced magnetic resonance imaging.

Then they begin individual and group therapy sessions, with the mask serving as a conversation starter. “Often people with post-traumatic stress have a hard time putting into words what they're trying to say, but they can be more expressive with a visual medium,” says Chatterjee.

At the end of the program, the veterans create a second mask, which is then evaluated by a focus group. “We essentially used a crowdsourcing approach to assess the masks, where the people evaluating them didn’t know which masks were from the beginning or the end of the therapy.”

To help the assessment group describe the masks in more detail, Chatterjee gave them a tool in the form of a taxonomy. It consists of 69 terms he and his colleagues from the fields of art history, neuroscience, philosophy, psychology, and theology have developed together to help people query themselves when putting the feelings and meanings art can evoke into words—which can be difficult.

"It's a general principle in psychological research that we're better at matching something than generating it on our own. For example, you might say, 'I'm feeling something, but I'm not sure what it is. It's not great, but maybe not so bad either.' Then, I give you terms like 'worry' or 'melancholy,' and you might say, 'No, it's not worry. It's melancholy. That fits what I'm feeling.' We believe that giving people this taxonomy is helpful, and we use it in many of our studies.

In the case of the mask experiment, we could show that the initial masks were described as being more agitated, while the later masks, after therapy, were calmer."

To support the findings, Chatterjee and his team also looked at whether there were differences in the brain patterns of another group of people who received therapy and showed some signs of psychological healing in their masks compared to those who didn’t.

Those who showed an element of closure in their masks had a stronger connection between the areas in the brain responsible for attention, memory (hippocampus), and pain processing (insula, thalamus, postcentral gyrus). Remarkably, in the group of people who benefited from the therapy, researchers observed a difference both in the interpretation of the masks and in brain activity.

Beyond Words: Helping Children Process

Trauma Through Art

Traumatic experiences like war, which are already hard for adults to put into words, are even more difficult for children to express, as their verbal abilities are still developing. This makes art therapy so effective for kids, especially younger ones. In Ukraine, where they have endured unimaginable losses and violence due to the ongoing conflict, the Litokryl camp by nonprofit Rescue Now supports children to express their emotions through art while dealing with post-traumatic stress.

The two week psychological program at the camp consists of three parts: art therapy, therapeutic group sessions, and individual counseling. Before the camp, each child undergoes a screening interview with a psychologist, during which they assess the family situation, the child’s emotional state, and the risks of developing post-traumatic stress disorder.

The exhibition "Healing" showcases a series of collages that combine children's portraits, their drawings, and the stories behind each creation. Learn more about the project here.

“Art is an accessible way to introduce children to therapy and ease them in”, says Maria Shabalina, the lead psychologist of the Litokryl project in an interview with The Overview. “In Ukraine, people don’t usually talk about the experiences that cause them pain. And so the parents normally don’t give their children an explanation of what had happened to them and why a situation brought pain. So normally, when the children first come to our therapy sessions, the first thing they say is that they’re okay and that they didn’t experience any trauma. They have suppressed their emotions."

Art can then serve as a tool to help them open up the brain's speech and language pathways that can be blocked by trauma. Maria remembers a group art therapy session in which the children were asked to draw an event they don’t want to remember, but that keeps intruding their minds. They were free to draw it literally or metaphorically.

One boy painted the whole paper in red and added black tear drops on top. Initially, he refused to talk about what he had just drawn. However, later in the session, he opened up and shared that the traumatic event he experienced was witnessing how his father was being tortured, with the whole family forced to watch.

“When I asked him why he decided to share it, he said because he realized that there are other children who have experienced similar pain and that it made him feel less alone.”

Maria further explains that children's brains are more adaptable and flexible, making them more open to change. This is why offering support directly during ongoing traumatic experiences and early in life can help foster resilience.

“After participating in the therapeutic groups, children begin their journey of healing. What they experience and process in the camp, they carry with them into their families.

The full-scale war in our country has been going on for over three years. Of course, it’s impossible to fully restore a child’s emotional state in just two weeks.

However, our program is designed in a way that gives children tools for self-regulation, like breathing techniques, which they can continue to use after the camp ends.The goal of Litokryl is not only to provide emotional support and help restore the children’s psychological well-being, but also to give them back a sense of childhood.”

Art as Medicine: Managing Chronic Pain

In addition to benefiting us psychologically, the arts also have a positive effect on our physical health. A recent UK report by Frontier Economics studied the impact of mindfulness-based art therapy involving drawing, painting, bookmaking, and meditation on female patients with breast cancer.

It showed that engaging in a creative activity helps alleviate chronic pain, lower stress levels and improve quality of life for patients in paediatric care. However, researchers in neuroaesthetics are still trying to understand the underlying neurobiological mechanisms that make art therapy so effective to design personalized treatment plans.

The same study further shows that engaging in aesthetic activities can also have preventive benefits and could ease the financial burden on the healthcare system. One of the findings showed that adults aged 50 and over who engage with cultural venues like theaters, concerts, cinemas, art galleries, and museums have a reduced risk of depression, with an estimated per person benefit of around £314 per year (approx. $393) and a substantial societal benefit of about £3 billion per year (around $3.75 billion).

Spaces That Heal: Neuroaesthetics in Architecture

Just as engaging in art and culture can help us heal, the spaces we live in also affect how we feel. Aesthetic experiences constantly happen all around us. As Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross further write: “The light in the room, the sounds around you, the smells—these are aesthetics, as potent as a Picasso or a Rothko.”

This is especially true in places like mental health hospitals, where patients arrive at their most vulnerable. Many of these highly managed, functional spaces have bright lighting pouring down from overhead fixtures, the walls painted beige, the furnishings sparse. They feel unwelcoming, often lacking a sense of care.

“We spend 90% of the day indoors. The built environment has a great effect on our mood, mental state, and well-being. Spaces that are purely functional risk dehumanizing people. To design buildings that foster well-being, we have to focus on the people inhabiting them,” explains Anjan Chatterjee, who also conducts research in the field of neuroarchitecture, a subdiscipline of neuroaesthetics that explores our neural responses to the spaces we inhabit.

As he points out, our old brains are stuck in a new environment. They evolved during the Pleistocene, over the span of around 1.8 million years, in which we lived in natural environments. So it’s only in the last 10,000 to 12,000 years that we've been living in dense cities like New York.

This might explain why we feel more at ease in buildings that bring the outside in. Chatterjee is currently designing “refresh rooms” based on biophilic design principles for Alpas Wellness, a new mental health facility in Maryland. The idea is to create two spaces for patients and staff to see if this kind of environment has a positive effect on the regulation of their emotions.

Hospital Rooms: Creativity, Care and Kindness

But what about publicly funded facilities with limited resources, many of which are several decades old? How can these functional-first facilities, often run-down, be cost-effectively transformed to promote wellbeing?

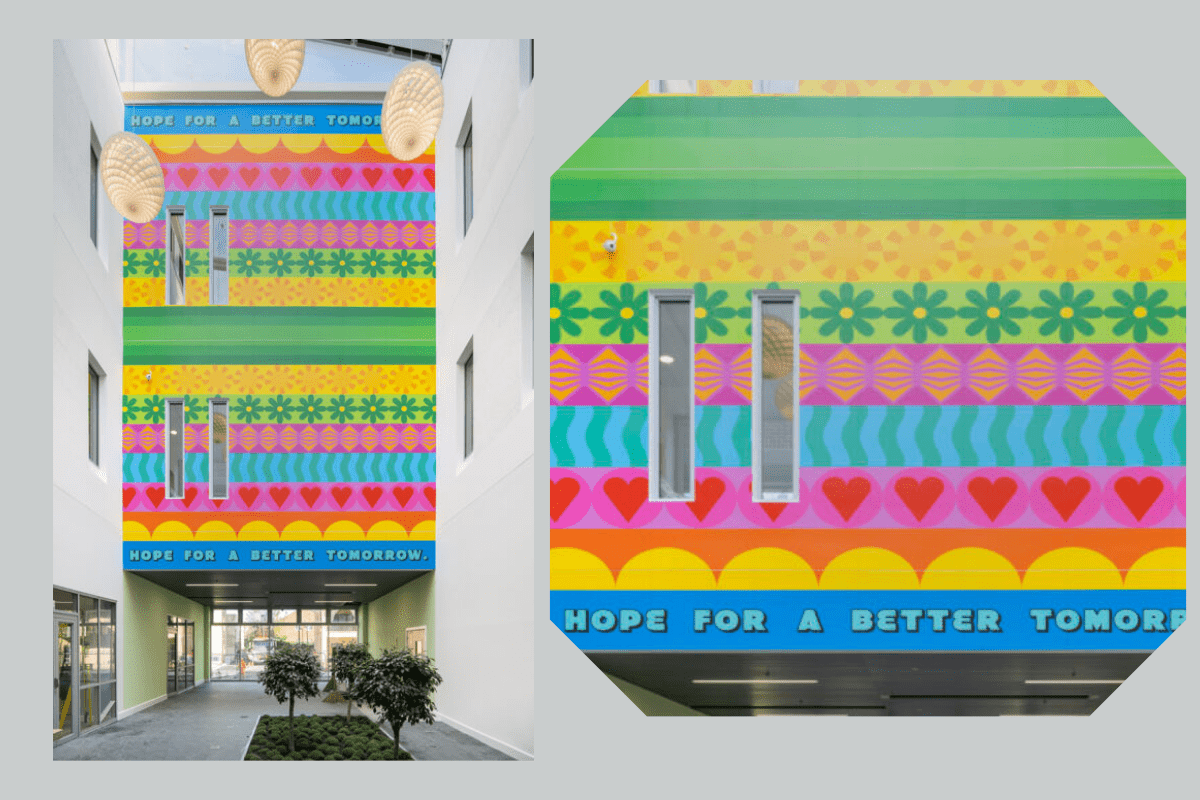

In 2016, artist Tim A Shaw and curator Niamh White asked themselves the same question after visiting a close friend who had been admitted to a mental health ward following a suicide attempt. They were shocked to find the hospital environment was “cold and clinical”.

Having worked over 10 years in the art world, the couple had the idea to leverage their experience and network to bring gallery-worthy artworks to inpatient mental health units across England.

But when they first approached NHS facilities, decision-makers were sceptical. It was considered too risky to bring outside communities into these highly secured spaces. Some even feared patients could vandalize the artwork, showing the stigma that can exist within the mental health system itself.

Today, almost 10 years and 200 artist commissions later, the majority of artworks are still there and in very good condition and Hospital Rooms has since received an overwhelming number of collaboration requests from NHS facilities.

Over the years, the nonprofit has brought world-class artworks by renowned artists such as Sutapa Biswas, Sonia Boyce, Nick Knight, and Anish Kapoor into mental health wards; along with a sense of dignity and imagination.

“When we start working on a project, we take a very nuanced approach, as every community and environment has different needs,” explains Haley Moyse Fenning, Hospital Rooms’ Head of Impact, in an interview with The Overview. “That’s why we begin with a research and development phase before starting with the participatory process. The findings then help inform which artists and artwork we would like to bring into the hospital community.”

A research method the nonprofit uses is called Photovoice. “We give patients disposable cameras and ask them to take pictures that mirror their experiences with the ward.

One example that really stood out to me was one patient who took photos of all the signage that told him what he couldn't do, things like, 'Please keep off the grass,' 'Don’t press this button,' 'Do not enter.' He built up this catalogue of restrictions through these visual pieces.

Then, we asked the patients to reimagine the space on top of the images they had taken. For example, with a white wall and a 'no entry' sign, we asked, 'What would you want to see here instead?' This process helps reveal new ideas.”

After the research and development stage, a three- to six-month co-production phase follows, featuring creative, artist-led workshops with the patient groups. The themes, ideas, and colors assembled in these sessions inspire the final artwork, ensuring that it reflects and evokes the experiences had in the workshops.

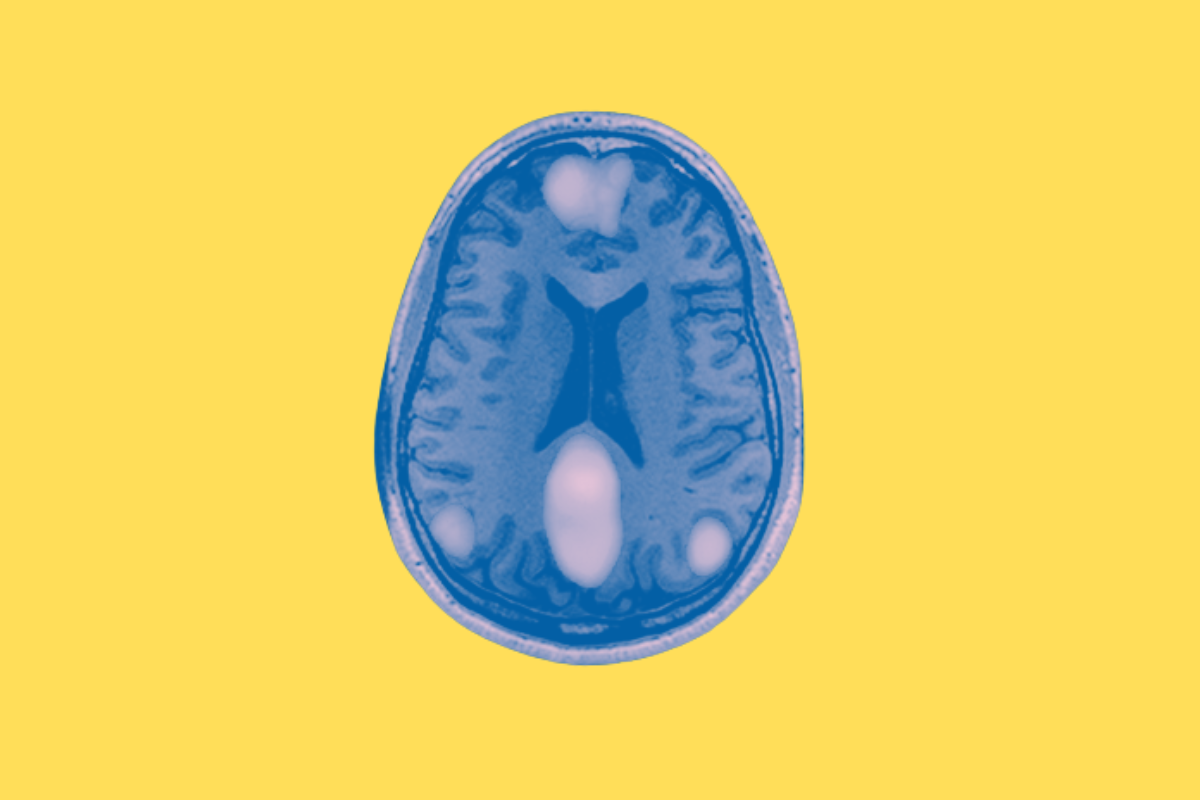

“One of my favourite examples is a beautiful, expansive atrium piece in Springfield Hospital, in South London. The mural titled “All around me, my gathered star” was created by conceptual artist Sutapa Biswas. She worked very closely with the patient group to identify the blue color and to think about themes around the stars.”

Learn more about Hospital Rooms' upcoming projects.

During the workshops the patients also created their own artworks. They learned about creative approaches, methods, techniques, and more directly from Biswas and had access to all the art supplies they needed.

“Patients also connect with each other in a space outside their normal routine to engage in creative activity. Then their ideas are being taken forward into an artwork that will live in perpetuity, and that others will be able to benefit from” says Haley.

Another crucial aspect for Hospital Rooms is measuring the impact of their work on both patients and staff. A method the nonprofit uses to track the transformation of the environment from beginning to end is called Visual Matrix. Before a project starts, a focus group mostly consisting of staff members is guided through the space given prompts that encourage them to come up with associations of the environment.

“We often hear in these sessions that the environment seems ‘dark,’ ‘uncared for,’ ‘dilapidated,’ and ‘lifeless.’ At the end of the project, we run through the same prompts and questions with the same staff to see how they perceive the space with the artworks in place. The new answers are very different and range from ‘It's come back to life,’ and ‘It's bright,’ to ‘We are seeing people have conversations in these spaces.’ This area that we heard nobody ever went into is now where patients take their visitors when they come in.”

In addition to measuring the impact a project has had, Hospital Rooms is currently also collaborating with scientists through the Hospital Murals Evaluation (HoME) project, a research initiative between NYU Steinhardt, CultuRunners, and the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe.

The project brings together a multi-country study approach with findings from Slovenia, New York, UK and Nigeria, where Hospital Rooms has found a second home thanks to the artist Nengi Omuku, who has been collaborating with the charity for several years. Inspired by the experience, she set up a similar organisation in Lagos, named Ona Iwosan (The Art of Healing).

“The purpose of the HoME study is to examine the impact of murals within hospital settings across multiple countries and various healthcare communities for a broader understanding of the effects of art in different cultural contexts. The outcome from this research will be published in Autumn this year, however, first findings show that the participatory element is very important. Real impact occurred when patients or hospital communities had the opportunity to contribute to the mural in some way, which was very validating for us.”

The Crucial Role of Research

Architects and designers could benefit from Hospital Rooms’ approach to iterative research, in adapting the built environment to better meet the needs of its inhabitants.

As Chatterjee points out in an interview, many architects make prediction errors. They try to imagine how people will feel and behave in the spaces they design, but little research is done to verify whether their assumptions were correct, as feedback is rarely collected once the building is in use.

“For neuroarchitecture to mature and have a solid foundation, it needs to be grounded in research where people are doing experiments and not just saying, “This is how the visual system works” or “This is how spatial navigation works, and we should apply this idea to the built environment.” That’s fine, but the field will wear itself out in the long run if not animated by a robust research program.”

The Arts: A Need to Have

Highlighting the importance of thorough scientific research combined with a better understanding of human experiences can reveal new insights that contribute to transforming healthcare and education.

Neuroaesthetics is the bridge that reconnects science and the humanities, the so-called “two cultures”, as coined by British scientist and novelist C. P. Snow—which have remained largely separate since the Industrial Revolution.

Around the world, a growing community of neurologists, physicians, artists, psychologists, philosophers, institutions, art historians, designers, and architects collaborate to better understand the benefits of the arts—showing that they are not just a “nice-to-have”—but a “need-to-have.”

Or as Leonardo da Vinci put it: “To develop a complete mind: Study the science of art; Study the art of science. Learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.”