New Zealand freediver William Trubridge’s determination to overcome human limits one breath at a time has granted him several world records reaching depth up to 124 meters. In this interview he speaks about his connection to to the sea and how freediving can benefit our mental well-being.

Although many of us feel disconnected from the ocean we are drawn to it at the same time. Where do you think that fascination originates?

William Trubridge: I’ve asked myself that many times too, and it’s a mystery to me. Why are we drawn to the ocean? Why do we want to spend our vacations at sea? Property on the waterfront will refer to ten times as much as it does in the countryside. I don’t have an exact answer, but theories are suggesting that it might have to do with our distant past, having evolved from the oceans. We spent the first nine months encased in the womb, swimming in liquid. I think it is somehow profoundly embedded in our psyche. We like to see things that are in motion rather than static. But I still feel there’s more to it. So many books have been written specifically about answering that question. But I still haven’t heard of one theory that gets it right.

What were your earliest childhood memories of the ocean?

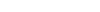

William Trubridge: I lived on a boat with my family, sailing from Europe to New Zealand for over five years. When we left, I was only two years old, but I started to form long-term memories somewhere along the way. The ocean was everything to us back then: highway, home, supermarket, school, and playground. I remember my father went spearfishing, and we would trail a hook behind the boat to catch Mahi Mahi. I think I’ve spent my whole life learning from the ocean.

William Trubridge trying to imitate his mother doing yoga on their yacht “Hornpipe”. Photo via www.williamtrubridge.com

What were some of the greatest lessons you’ve learned?

William Trubridge: For me, it’s the idea that we are, in essence, purely consciousness and nothing else. Being underwater takes away the memories of the past and the worries about the future. You are here and now. You are just a presence, an awareness watching and experiencing everything as it comes through the window. You transform into an aquatic being by stripping away all of that terrestrial distraction so that you can experience what it is to be pure consciousness. That’s probably the most important lesson the ocean has taught me during my freediving career.

In which part of the dive are you experiencing this state the most?

William Trubridge: The way that I would experience that in its purest form would be during a dive we call deep hangs, where I’ll go down to a middle depth of around 60 meters and stay there, holding on to the rope completely relaxed. That allows me to go inside myself and experience this form of awareness the most.

How has the mental aspect of freediving affected your personal life?

William Trubridge: People say that I have a calm personality. And I guess I usually don’t react to negative situations and scenarios in an extreme way. But with a lot of emotional outpouring, I still feel probably all the same emotions as everyone. And sometimes I can control them, and sometimes I can’t. I try to employ those negative emotions, whether it’s anger, irritation, or frustration, as information being sent from one part of my brain to another.

It’s similar to experiencing the urge to breathe underwater, which is a very intense sensation. But I’ve learned that this is also just information about two different gases in my bloodstream, carbon dioxide and oxygen, carbon dioxide going up, oxygen going down. So if I can see it purely as information, I can detach myself from that reaction to it. And so it helps me to stay longer underwater. The one thing that I often get back to and that I’m constantly in the process of seeking out is equanimity, the ability to be in difficult situations while still staying centered and focused, and calm. And freediving has helped me improve in this field.

How long can you hold your breath underwater?

William Trubridge: If I’m not moving, the longest I’ve held my breath was eight minutes. But typically, during free dives, the longest would be between four and four and a half minutes. We’re more flexible in the lungs through breathing and other exercises to accommodate more air or accommodate more pressure when that air gets compressed.

Training extends that, and we get to the depths of 100 meters and beyond through exercise, but everyone has this capacity and can hold their breath for longer than they think. We all have a mammalian dive reflex, an innate response to holding our breath that prolongs the time we can be underwater.

Right before the dive, you lay still on the water’s surface. What are you doing at that moment? Do you practice some form of breathing technique that allows your body to take on more oxygen?

William Trubridge: It’s not about taking on more oxygen. That’s an essential concept that I was trying to clear up in interviews before because people think that we’re oxygenating ourselves. And that’s not the case. As you are now, your blood is fully oxygenated. You cannot fit more oxygen into your blood with any particular breathing technique. And when we’re preparing before the dive, the focus is actually on not breathing too much. Because if you inhale too much, then you lower your carbon dioxide level. And you need some of that gas to trigger the mammalian dive reflex that helps you conserve oxygen. So in the preparation, it’s only about relaxation and making sure that you don’t over-breathe.

How would you describe your mental state before the dive, laying on the water’s surface?

William Trubridge: Your mind tries to throw in these negative thoughts like: “This is the last breath you’re gonna take” or “you will blackout.” But like I mentioned before, it’s crucial not to combat these thoughts but see them as information. There is a quote by Zen monk Shunryu Suzuki that resonated with me: “Leave your front door and your back door open. Allow your thoughts to come and go. Just don’t serve them tea.” So I just let them slide through without trying to fight them because that would make them stronger. These moments before the dive are probably the most challenging mentally.

And which part of the free dive do you most enjoy?

William Trubridge: When you reach a depth of about 20 meters, the freefall sets in, which is probably one of the most beautiful parts of the dive. You are accepted into the ocean. Your lungs have been compressed to the point where your body is negatively buoyant. So you can stop swimming and still fall at a significant speed close to a meter per second. And that means that you can relax and allow yourself to be drawn down deeper into the ocean to reach a trancelike state, and the depths and the darkness will help you to do that. If you carry on swirling, you’d be wasting energy. And then, when you turn around, you’d have less energy and oxygen to come back up. So you’re conserving everything for that ascent, which will be a lot more complex than your way down, where you only take seven strokes before freefall. On the way up, it can be as many as 30 to 35.

So you have to swim efficiently. If you swim too quickly, then you’re going to waste your oxygen. If you swim too slowly, you’ll be economical in your movements, but you’ll be under the water for so long that you’ll be using more oxygen because of that. So this is a fine-tuned balance that you need to find and the speed at which you come up.

I’ve read that you once lost consciousness on your way up and the safety divers had to step in.

William Trubridge: We call that a blackout, where you become unconscious underwater because your oxygen has dropped to a level at which your brain is shutting down. You can compare it to a computer. When it gets to a low battery, it shuts itself down to conserve the remaining energy. The brain shuts itself down with still quite a lot of reserves left. So even if that happens, the safety divers get you to the surface. Typically the unconsciousness lasts only a few seconds. It looks gruesome, but in reality, it’s not a massive threat to your life. We want to avoid it because it’s a failed dive. And if you push too hard, you’ve screwed something up. But at the same time, if you are pushing limits trying to break world records, it will happen sooner or later. So it has happened a few times in my career. And the most critical thing afterward is to analyze what went wrong. So that you can use that to improve and make sure it doesn’t happen again.

You just mentioned that you are trying to push limits. Especially when you are competing on such a high level, you are taking calculated risks, and through professional training, you can minimize them. But in depths up to 100 meters and more, you’re entering a hostile environment that the human body isn’t designed for. How do you notice your body’s boundaries in time?

William Trubridge: With experience, you develop a delicate perception of those boundaries. I was training this morning, and it wasn’t my deepest dive, but it was still very deep. On the way up, I started to get a sense that I wouldn’t make it. Usually, that’s when I persist a little longer to see how it goes. If it intensifies, then I can abort the dive. So in my case, if I’m coming up, I can start to pull on the rope, which makes the drive a lot easier, and also signals to my team that I’m aborting the dive. And so they can activate the cannabis, which pulls the rope up quicker. So then, all I have to do is hold on to the rope and get a free ride back to the surface. But even if I push it a little too far and I blackout under the surface, my safety team is right there. It’s not going to happen at the maximum depth. Because when I turn around at the bottom, I still had more than half of my oxygen left. If I screw it up, if I misjudge it a little bit, it’s going to happen right at the end of the diaphragm close to the surface. So even though it seems like we’re pushing the envelope and risking our lives, it’s not necessarily the case.

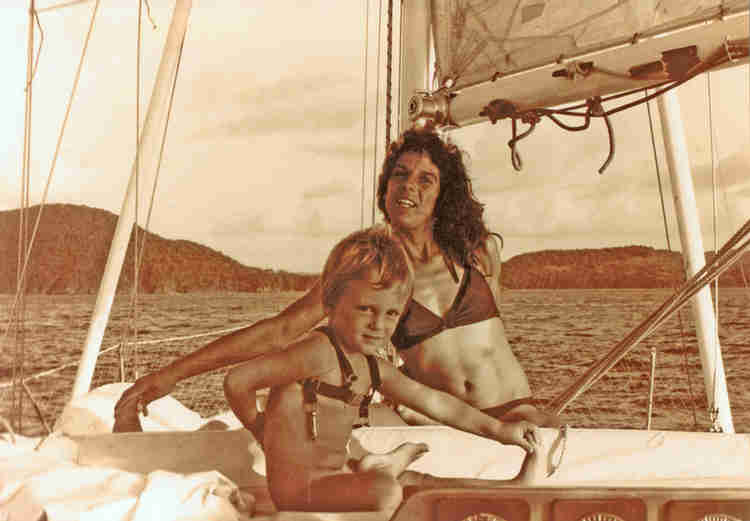

William Trubridge relaxing in Dean’s Blue Hole in The Bahamas where he lives and trains. Photo by Sachiko Fukumoto

Change of perspective: Dean’s blue hole from above. It’s easily accessible from the shore and is said to be 202 meters deep.

In the past, there were also some deadly accidents.

William Trubridge: In almost all of the accidents that have happened, the safety system has failed, and athletes have been pushing up against other kinds of injuries like lung injury or something else that has made the dive more dangerous. But in a controlled scenario, diving with a good safety team shouldn’t be too risky.

Freediving is a relatively young discipline. How do you see the sport evolve in the future?

William Trubridge: It’s been around for a little while, since the 50s or 60s. That’s when people started setting world records. But in terms of competitions, it’s relatively recent; I’d say it has only really picked up in the last 15 to 20 years. So there’s still scope for it to evolve and to become more mainstream. The safety side needs to stay concurrent with that and also keep up. But I think we’re heading in the right direction. And I think it will change a lot from the format that we have now. So the primary disciplines that we have diving with fins or without fins are the two best definitions of human potential. And I see those as remaining the two main ways of freediving in the future. We still have to understand more about physiology, what’s happening in the lungs in particular, and what causes accidents. We also need professionally trained safety divers who meet certain standards.

What is your greatest motivation when it comes to developing the sport further?

William Trubridge: The most significant incentive for me is to redefine what we can do underwater. Every other water sport you can think of, like swimming, sailing, and surfing, takes place on the boundary between air and air-water. In swimming, for example, you are lifting your arms or your legs out of the water to recover them so that you can move faster, taking breaths from the air. It’s a semi-aquatic discipline. And that applies to every water sport that we have at the Olympics. But freediving is the only true definition of human aquatic potential because you’re entirely immersed underwater for 100% of the performance.