Dr. Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology and director of UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, has researched the emotion of awe for over 15 years. In his latest book, “Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life,” he shares the latest findings into a sensation we all experience but hardly understand.

In your book, you mention eight sources of awe: moral beauty, collective effervescence, nature, music, spirituality and religion, life and death, epiphany, and visual art. What were your personal experiences with awe-inspiring art?

Dr. Dacher Keltner: Growing up with my dad being a visual artist, I spent much of my childhood immersed in museums and surrounded by his paintings. And I remember visiting the Louvre in Paris with my family. Initially, my younger brother and I weren’t interested in the artworks. My dad suggested that we take a closer look at the Dutch masters’ paintings in room 837, specifically those by Johannes Vermeer, Jan Steen, and Pieter de Hooch. I don’t recall the exact setup in 1977, but I’ll never forget the quiet ambiance surrounding these paintings – the lighting, the subtlety, and the tenderness of the expressions. Seeing de Hooch’s pieces depicting everyday affairs, such as women cooking, doing laundry, petting dogs, picking lice out of children’s hair, or raising a glass of ale in the community of friends, changed how I see the world.

One of Dacher Keltner's favorite painters–Pieter de Hooch: A Woman Drinking with Two Men(1658)

In which way?

Dr. Dacher Keltner: For the first time, I became fascinated by the idea that you don’t have to climb a mountaintop or engage in a blissful meditation exercise to experience awe. It’s in the simple things, the everyday moments, that often go unnoticed. I write about this a bit, and I think it’s because of my parents’ challenging marriage and my struggles as an unhappy adolescent. Though I felt alienated most of the time as a teenager, I, too, would experience sublime community over a beer with friends. De Hooch opened my eyes to the idea of everyday awe.

In your book “Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life”, you describe that we feel awe when we experience something vast and mysterious that transcends our understanding of the world. Where do we find that in de Hooch’s paintings depicting the seemingly mundane scenes of everyday life?

Dr. Dacher Keltner: The Dutch masters’ use of light was very striking. It made me think about the light surrounding us, which we now know from physics is a complicated and mathematically mysterious force originating from the Big Bang. As someone with scientific training, I tend to have a more rigid and analytical mind, but looking at these paintings always made me aware of the vastness of things beyond our understanding. I had a profoundly personal experience with light when my brother passed. His face was entirely illuminated, and it felt like his soul was moving toward a different dimension beyond my narrow perception.

Pieter de Hooch: Woman With a Child in a Pantry (1658)

You write about how art can destabilize our concepts of reality and evoke awe. Can you please expand on that?

Dr. Dacher Keltner: The central thesis of one of the pieces in my book, supported by cognitive science, is that our minds constantly seek a stable understanding of reality and social concepts, for example, capitalism, gender, war, or sexuality. However, we often need to correct these fixed beliefs and adapt to changing circumstances.

When what we encounter in art aligns with our minds’ default expectations, we feel at ease. On the contrary, it can be awe-inspiring when artists challenge our beliefs about reality. For example, I write about the artist Susan Crile, who reproduced photographs of prisoners tortured at Abu Ghraib in a series of drawings. They reminded me of how those photos initially shook our understanding of reality about the military and American foreign policy when the media released them in 2003.

Crile’s work on torture portrays the horror and trauma in a way that can evoke awe because it’s difficult to grasp why people would torture each other, and it’s vast, subjugating another person’s life. That’s how visual art can challenge us to rethink reality and consider new ideas about ourselves and society.

As a scientist, you also study our biological response to experiencing awe in art. What happens in the brain while looking at, for example, an awe-inspiring painting?

Dr. Dacher Keltner: Researchers still need to fully understand the physiology behind art appreciation. However, art activates dopamine release, which connects to our desire for exploration and novelty. So when we encounter a novel representation of reality through art, it can open up our minds and bodies by triggering dopamine release.

Studies in neuroaesthetics have identified four ways visual art can make us feel awe. When we view a painting, neurochemical signals travel to the visual cortex, which constructs rudimentary images. These signals then activate regions of the brain related to object recognition. Artists can use optical techniques to stimulate our contemplation of ideas and concepts.

Next, the neurochemical representation of visual art activates networks of neurons, for example, in the anterior cingulate cortex, and bodily sensations, evoking direct, embodied experiences. Finally, the prefrontal cortex assigns meaning to art based on culture and personal experiences.

Dacher Keltner of the emotion of Awe.

You also mention that art reveals the patterns of nature and our social life. In which way?

Dr. Dacher Keltner: One of the most valuable things humans can do is recognize and understand the patterns around us. Art is a powerful tool for teaching us to recognize them. For example, think of Sebastiao Salgado’s photos of 50,000 men grafting in Brazil’s Serra Pelada gold mine. These images visualise the patterns of extraction-based capitalism that reduces human beings to means of production.

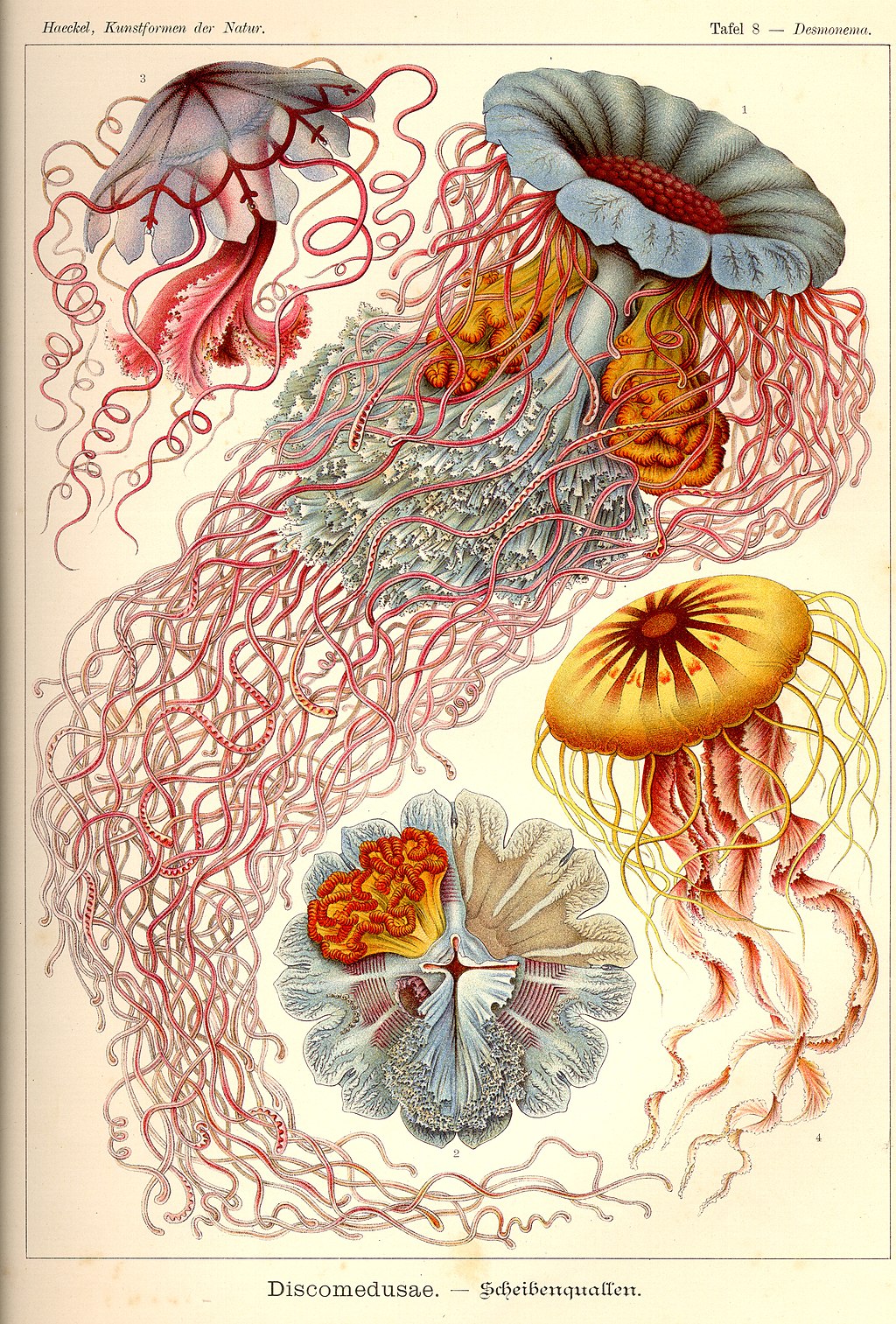

An example depicting the patterns in nature is the detailed illustrations from 1904 by Ernst Haeckel of jellyfish, sea anemones, clams, and fish. The artworks allow us to experience the symmetry and geometry of nature and enable us to see Darwin’s idea about the evolution of species from earlier primordial forms. So art trains us to become more sophisticated pattern detectors, which can enhance our understanding of the world around us.

Ernst Haeckel, Kunstformen der Natur

You mentioned a study that links engaging in art to higher levels of empathy and civic engagement. How do you explain that?

Dr. Dacher Keltner: That was a large-scale longitudinal study. It found that the more people engage in art, the more committed they are to their community. They tend to trust more, show more empathy, and engage more in civic activities. Additionally, studies show that art therapy is effective for handling mental health issues, and areas of cities with more visually pleasing designs can improve people’s moods.

In Europe, for example, urban planners design cities much better, and there is a lot of public art and community music, bringing people a sense of shared humanity. I think it’s evident that walking around in public squares and taking in the culture, is beneficial for one’s nervous system and can trigger the release of oxytocin which has a positive effect on our behavior towards others.

How would you define the purpose of awe from an evolutionary standpoint?

Dr. Dacher Keltner: Many emotions like gratitude and compassion can unite people, but awe serves a unique purpose. It creates a sense of collective, making you less self-focused, which is essential in building a solid community. For example, when we experience the vastness of nature, we feel small. Awe is a humbling experience that reconnects us with the world around us. The same happens when we attend a musical event; we will feel a shared connection with the people around us. That feeling of community inspires us to take actions that benefit the group.

Additionally, awe opens our eyes to the intricate systems of life. By experiencing wonder, we become more aware of them, such as our social and environmental systems. This cognitive shift towards systems thinking is a remarkable achievement of the mind. It helps us understand our place in the world. So, in summary, awe lets us build community and encourages us to appreciate the systems we are part of.

What I found striking was your research on moral awe and how it’s a universal experience all humans share.

Dr. Dacher Keltner: Yeah, it’s incredible how we’ve discovered through research in 26 countries that the moral beauty of other people, often ordinary people, is the most reliable source of awe. Their sacrifice, generosity, courage, and ability to overcome challenges like poverty or mental illness are awe-inspiring. Even more interesting is that these qualities are essential for healthy cultures. We need to follow these rules of selflessness, courage, sacrifice, and giving to others.

Emotion wires us to feel moved by witnessing other people’s acts of selflessness. This contagious behavior becomes an important part of our culture that we share through storytelling, legends, literary fiction, music, and art to help people appreciate the importance of being generous and self-serving. This research has revealed how our imitative responses to people’s selflessness go beyond other mammals and contribute to creating a healthy and cohesive society.

A whole school of thought suggests that religion or society derives our morality or constructs it, which is partially true. However, important aspects of moral beauty, such as sacrificing and sharing, are universal and evoke a deep intuitive response.

You also mention that the mindfulness movement tends to focus self-centeredly on introspection instead of looking outwards. While this is often beneficial, there are also potential drawbacks to this individualistic approach.

Dr. Dacher Keltner: It seems we are overly focusing on the self. We spend too much time staring at ourselves on Zoom, taking selfies, going to therapy, and discussing the self. In the mindfulness movement, many popular practices emphasize going inward.

While becoming aware of our bodies is crucial, we also must contemplate and reflect on the external world. Awe is an excellent way to shift our focus from the self to the world around us. When we experience awe, we ask ourselves questions like: “What is this painting saying about war or love?” Or: “What is the environment telling me about the health of the planet?”

We also need to shift our attention toward people and culture. We must make these shifts in our contemplative orientation. I think awe is a fantastic way to achieve this because it encourages us to look beyond ourselves.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.